魏晉南北朝時期,從東漢滅亡到隋朝統一中國,時間跨度約400年。在這個以戰爭和衝突為標誌的漫長時期,留下來的物品並不多,因此就中國的藝術史而言,它長期以來一直是一個鮮為人知的時代。

本次展覽旨在展示從青瓷技術的全面實現到作為青瓷生產產物的白瓷的藝術創作流程。北齊對白色大理石雕塑的偏愛可以看作是中國對「白色」追求的一部分。

這種追求始於早期的商朝,並導致了白色陶器的生產。它也可以被看作是一個延伸的審美過程,最終導致隋唐時代對白瓷技術的追求和完善。

隨後的初唐王朝對白色大理石的類似熱愛也標誌著白瓷全面繁榮的時期。展覽中的陶俑部分主要展示了今天因其藝術性而備受矚目的北魏作品。

北魏陶俑與日本飛鳥時期的佛教雕塑有許多共同點,這些共同特點使陶俑更容易接近和吸引日本的觀眾。本次展覽還展出了許多與佛教有關的作品,這些作品以青銅、石頭和泥土等不同媒介製作。

青瓷是中國陶瓷中最受歡迎的形式之一,在東漢末年至三國時代首次成功燒制。然後,東晉時代產生了書法家王羲之和詩人陶淵明,他們的作品在後來的幾個世紀里對中國和整個東亞文化圈都有巨大的影響。

北魏是一個成為古代日本政治和行政模式的朝代,因為它開始形成自己的全國性結構。在這400年的時間里,隨著朝代和王國的興衰,人們創造了無數的文物和藝術作品。

我們不能忘記、否認,在這漫長的四個世紀中,受教育階層的智慧和他們制定的貴族文化支持、滋養了中國文明。

這些知識分子在東漢時脫穎而出,他們承認並支持曹操,而他們的文化影響在蘭亭集序中更是達到了充分的體現。

即使在戰爭和動亂的動蕩中,當時的人們也被吸引著去推進他們的文化。如果這個展覽能讓參觀者感受到,在那麼多世紀以前,藝術和文化是如何成為他們生活中極其強大的一部分,那是多麼美好啊。

魏晉南北朝藝術展

川島公之

1) 魏晉南北朝藝術概要 - 本次展覽的重點作品

秦漢以後,中國大地進入分裂時期。隨著東漢的滅亡,中國在220年左右分裂為魏、蜀、吳三國,這種政治局面持續了約370年,直到589年隋統一中國。然而,東漢末年 184 年爆發的農民黃巾之亂,可以說是導致東漢王朝覆滅的事件。

這意味著分裂控制的時期持續了大約四個世紀。西晉在這段期間曾短暫統一全國,但未能持久。因此,從 2 世紀後期到 6 世紀後期,這段時期的大部分時間都是王國的興衰更替,是一個政治動盪和混亂的時期。

The Arts of the Wei, Jin and Northern and Southern Dynasties Exhibition

Tadashi Kawashima

1) An Outline of the Arts of the Wei, Jin and Northern and Southern Dynasties

- Focusing on Works in this Exhibition

After the Qin and Han dynasties, greater China entered a period of political splintering. With the fall of the Eastern Han, around the year 220 China split into three kingdoms, the Wei, Shu and Wu, a political situation that lasted for around 370 years until the Sui unified China in 589. However, the peasants' Yellow Turban Rebellion that broke out in 184 in the late Eastern Han dynasty can be considered the event that led to the fall of the Eastern Han dynasty. This means the period of splintered control lasted approximately four centuries. The Western Jin briefly unified the country during that time, but it did not last. As a result, the majority of this period from the late 2nd century through the late 6th century saw a succession of kingdoms rise and fall, making it a time of political upheaval and confusion.

Generally, the approximately 370-year period between the reign of the Qin and Han dynasties until the beginning of the Sui and Tang dynasties is known as the Six Dynasties period. In precise terms, the term refers to the rulers who established their capital in Jiankang, or Jianye, (present-day Nanjing), namely the Eastern Wu (222-280) and Eastern Jin (317-420) of the Three Kingdoms period, and the Liu Song (420-479), Southern Qi (479-502), Liang (502-557) and Chen (557-589) of the Southern Dynasties. Consequently, while the Western Jin, Northern Wei and Northern Qi were not part of the Six Dynasties, the period from 222 to 589 when the above-named rulers had Nanjing as their capital, is known collectively as the Six Dynasties period. This exhibition, however, includes artworks from the Northern Dynasties countries of the Western Jin, Northern Wei and Northern Qi, and as such we have chosen to call this period the Wei, Jin and Northern and Southern Dynasties period.

一般而言,從秦漢之間到隋唐之初的約 370 年間被稱為六朝時期。準確地說,是指建都於建康或建業(今南京)的統治者,即三國時期的東吳(222-280)、東晉(317-420),以及南朝的劉宋(420-479)、南齐(479-502)、梁(502-557)、陳(557-589)。

因此,雖然西晉、北魏和北齊不屬於六朝,但上述統治者以南京為都城的222年至589年這段時期,則統稱為六朝時期。然而,本展覽包括西晉、北魏和北齊等北朝國家的藝術作品,因此我們選擇將這段時期稱為魏晉南北朝時期。

When a nation stabilizes politically and is economically at its peak it is able to build a vibrant culture that in turn leads to the ample production of artworks. This situation can be seen to have recurred numerous times over the course of China's long history. In the field of ceramics, the Han, Tang and Song dynasties are exemplars of this trend. This does not mean, however, that splendid artworks were not created in the periods between these longer dynastic periods, in other words, during these more chaotic times. Indeed, we might even say that all the more richly creative works brimming with strange energy were made specifically because of those disturbing times. These works based on previously unfound concepts and ideas then became the basis for the works made in the following generation. This group of artworks from the Wei, Jin and Northern and Southern Dynasties period can be seen as representative of this trend, each harboring its own novel forms and ideas, and indeed, each important in terms of the history of art.

當一個國家政治穩定、經濟發展到頂點時,就能建立一個充滿活力的文化,進而帶來大量的藝術作品。在中國悠久的歷史過程中,這種情況可說是無數次重演。在陶瓷領域,漢朝、唐朝和宋朝是這一趨勢的典範。然而,這並不表示在這些較長的朝代之間的時期,換句話說,在較為混亂的時期,沒有創造出燦爛的藝術品。

事實上,我們甚至可以說,所有充滿奇特能量的豐富創造力作品,都是因為那些令人不安的時代而特別創造出來的。這些基於過去未曾發現的概念與想法的作品,成為後來世代作品的基礎。這批魏晉南北朝時期的作品可被視為這股趨勢的代表,每件作品都有其新穎的形式與意念,而事實上,每件作品在藝術史上都很重要。

First let us consider the ceramics of the Southern Dynasties, with celadon the core type of the time. Celadon is thought to have been first achieved during the mid Eastern Han dynasty in what is today northern Zhejiang prov-ince. This region is rich in both pottery clay and kiln fuel, with water transport also available. As a result the region flourished as a ceramic production site from antiquity onwards. Within Zhejiang province, areas such Shaoxing, Ningbo and Yuyao, which were part of the "Yue" territory during the Spring and Autumn Warring States period, flourished as celadon production sites. This area also saw the production of a high standard of products during the Tang, Five Dynasties and Northern Song dynasty periods, with the Yue kiln names found in numerous historical documents. Indeed, the products of this region's kilns are considered worldwide to be a pinnacle achievement in Chinese ceramics. In order to differentiate the works produced in the Yue kilns, in Japan, pre-Tang dynasty celadons are known as either Old Yue ware or Old Yue region celadons. This type is thought to have originated in the Eastern Han dynasty. Distinctive Old Yue ware forms and design motifs appeared, and the production of such works is thought to have attained a certain scale from the mid 3rd century onwards. At the end of the 3rd century, with the beginning of the Western Jin, this area became the center of celadon production both in terms of quality and quantity.

首先讓我們看看南朝的陶瓷,青瓷是當時的核心類型。青瓷被認為是在東漢中期在今天的浙江省北部首先實現的。這個地區有豐富的陶土和窯用燃料,也有水路運輸。因此,該地區自古以來就是陶瓷生產的繁盛之地。在浙江省內,春秋戰國時屬於越地的紹興、寧波、餘姚等地,也是青瓷的盛產地。

在唐朝、五代和北宋時期,這一地區的產品也達到了很高的水準,越窯的名字出現在許多歷史文獻中。事實上,這個地區的越窯產品在全世界都被視為中國陶瓷的巔峰成就。

為了區分越窯製作的作品,在日本,唐代以前的青瓷被稱為古越器或古越地青瓷。這種類型被認為起源於東漢王朝。在三世紀中葉以後,舊越器出現了獨特的造型和圖案,這類作品的製作被認為已經達到一定的規模。三世紀末,西晉初年,這一地區無論在質量上還是數量上都成為青瓷生產的中心。

The characteristics of Old Yue ware, thanks to advances in ceramic production technology, were a lessening of glaze surface irregularities and clearing of the formerly muddy glaze tones. This meant that wares were coated in an even flow of celadon glaze colored ash blue, bluish green or yellowish green. In terms of vessel shape, Old Yue ware saw the development of diverse vessel shapes and the creation of some works unique to the ware type. Burial trends were a major underlying factor in these developments. The aristocrats of this period competed amongst themselves to build the most sumptuous tombs, and large numbers of celadon grave goods were included in the burials. This trend increased from the latter part of the Wu kingdom of the Three Kingdoms period, with the peak period of the Western Jin seeing various different vessel types created as burial goods.

由於陶瓷生產技術的進步,古越瓷的特點是釉面不規則現象減少,以前渾濁的釉色變得清晰。這意味著器物塗上了均勻的青瓷釉,青瓷釉呈灰青、藍綠或黃綠色。在器形方面,古越器出現了多樣化的器形,並創造了一些古越器獨有的作品。

墓葬的趨勢是這些發展的主要基本因素。這個時期的貴族之間競相建造最豪華的墳墓,而大量的青瓷墓葬用品也隨葬其中。這種趨勢從三國時期的吳國後期開始增加,西晉的高峰期出現了各種不同類型的器皿作為殉葬品。

One such burial vessel type is the shinteiko (funerary urns, Ch: shenting-hu), which has a lively array of pavilions, jars, birds, animals and figures attached to the top of the vat form. These vessels are variously thought to have been prayers for bountiful harvests, longing for the realm of the gods and immortals, and reflective of the period's views of the afterworld. Shinteiko were produced from the Three Kingdoms period through the Western Jin. Plate 3, Celadon Funerary Urn, is an unusual example of these shinteiko, with Buddhist figures attached to the top of the jar. Only a very few examples of Old Yue ware works are adorned with Buddhist figures. It is also rare to find works with Buddhist figures playing a central role in the design scheme, and thus this is an important example that recounts how the Jiangnan region received Buddhist influence. This work has long been known as one of the major examples of the shinteiko vessel type in Japan.

其中一種葬具類型是神亭壺,在壺的頂部附有亭子、罐子、鳥獸和人物,生動活潑。這些器皿被認為是祈求五穀豐收、憧憬神仙境界以及反映時代對來世的看法。從三國時期到西晉,一直都有神亭壺的出現。圖版 3, 青瓷葬瓮,是這類神輿子的一個不尋常的例子,罐頂附有佛教人物。只有極少數的古越器作品有佛像裝飾。本壺是江南地區受佛教影響的重要例子。這件作品一直被稱為日本神亭壺的主要例子之一。

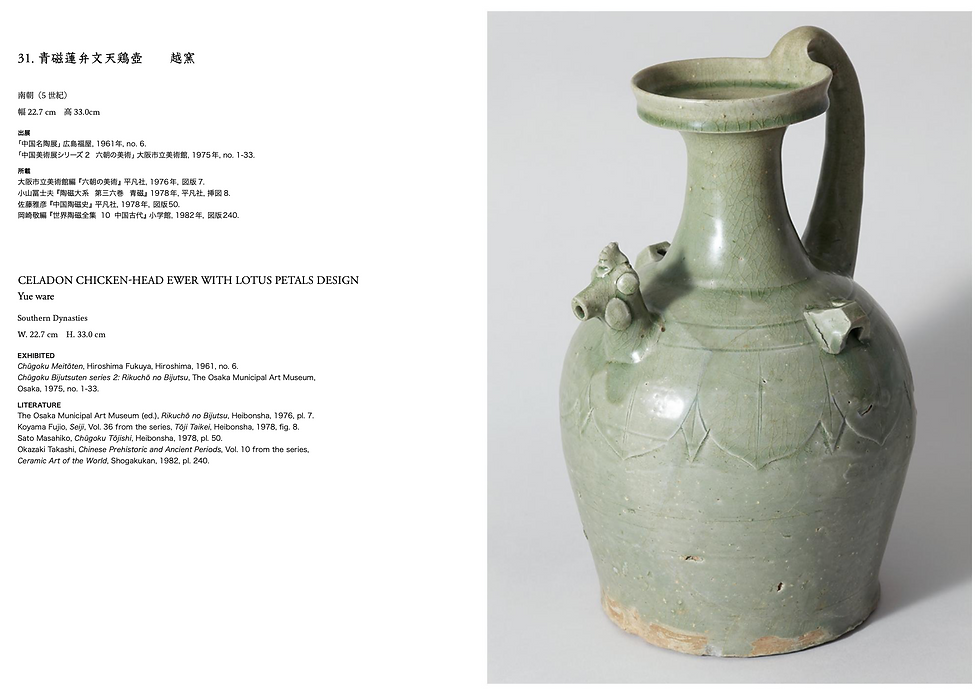

Another major vessel type is the tenkeiko (burial ewer with chicken-head spout, Ch: tianjibu). This vessel type was made over a long period, from the Western Jin to the Eastern Jin, and on into the Southern Dynasties, and as the type progressed, the neck was elongated and handles attached. This exhibition provides an opportunity to see how the vessel shapes changed over the time frame, see plates 6, 20, 24 and 31.

The unique nature of Old Yue ware is fully revealed in the works made in the form of animals. While there were the tenkeiko ewers with their chicken-head spouts mentioned above, this group is different, in that the vessels themselves are shaped like animals, namely in the form of sheep, tigers, lions and frogs. While they are animal in form, the incised wings on each animal indicates that they are actually divine animals, and scholars today believe the use of these forms had some ritual meaning. This issue has not yet been conclusively resolved. This exhibition includes frog-shaped vessels; see plates 5, 22 and 23. Among these, plate 5 is a particularly fine example of the numerous extant frog-shaped vessels. Vessels shaped like henhouses and pigsties, forms that had begun in the Han dynasty, can often be seen in Old Yue ware. The Celadon Henhouse seen in plate 4 is an adorable work featuring four birds inside a small round basket-shaped dovecote.

另一種主要的器型是天雞壺。這類器皿的製作歷時甚久,從西晉到東晉,一直到南朝,隨著類型的發展,頸部被拉長,並附加把手。本展覽讓我們有機會看到器形在不同時期的變化,請參閱圖版 6、20、24 及 31。

古越器物的獨特之處在於動物造型的作品。雖然有上面提到的雞首澆口的天雞壺,但這批器物是不同的,因為它們本身的形狀就像動物,即羊、老虎、獅子和青蛙。

雖然它們的形狀是動物,但每種動物身上刻有的翅膀顯示它們實際上是神聖的動物,今天的學者認為使用這些形狀具有某些儀式的意義。這個問題至今仍未有定論。本展覽包括蛙形器,請參閱圖版 5、22 和 23。

其中,圖版 5 是眾多現存青蛙形器皿中特別精美的一例。雞房、豬籠形的器物在漢代就開始出現了,在舊越器中也經常可以看到。圖版 4 所見的青瓷雞舍是一件可愛的作品,在一個小圓籃形鴿舍內有四隻鳥。

The work exudes all the fascinating characteristics of Old Yue ware.The Eastern Jin saw further new developments in Old Yue ware. The coloration of the celadon glaze improved to form a yellowish blue-green color, with many of the extant examples featuring smooth and glossy glaze. This period also saw a reduction in vessel surfaces decorated with stamped or applied motifs.

Compared to the Western Jin, there was a growing emphasis on items for actual use rather than for burials, an overall freeing from hardness and the production of soft vessel forms redolent of their clay origins.

這件作品散發著古越器的所有迷人特徵。東晉時期,越窯有了進一步的發展。青瓷的釉色有所改善,形成了淡黃色的藍綠色,許多現存的器物都具有平滑光亮的釉面。這時期的器物表面也減少了印花或貼花紋飾。

與西晉相比,這時期的器物愈來愈注重實際使用,而非用於殉葬,整體上也擺脫了堅硬的特質,製造出柔軟的器皿造型,讓人聯想到它們的泥土本源。

Celadon with iron oxide spots can be identified as one of the major types from this period. Iron spot celadons were created by dotting spots of iron glaze onto the unfired clay, coating it overall with a celadon glaze and then firing it. This process resulted in the impressive display of dark brownish spots that seem to float up here and there from within the celadon surface. This technique was seen from the Three Kingdoms period onwards continued in the Western Jin and flourished in the Eastern Jin. This type is said to be the start of the Yuan dynasty's form of iron-scattered celadon known in Japanese as tobi-seiji. This type can be seen in plates 19, 21, 22, 23, 25 and 28. Of those, the Celadon Box and Cover with Iron-Brown Spots at plate 28 is a sublime work in which this type's characteristics fully developed. This work is of course superbly formed, and the fact that only very few comparable examples exist make it all the more important.

帶氧化鐵斑的青瓷是這個時期的主要類型之一。鐵斑青瓷的製作過程是在未燒成的黏土上點綴鐵釉點,整體塗上青瓷釉,然後再燒成。這個製作過程讓青瓷表面浮現出深褐色的斑點,令人印象深刻。這種技術從三國時期開始就出現了,西晉時期持續,東晉時期發揚光大。

這類青瓷據說是元代鐵斑青瓷的開始,日本人稱之為飛青瓷 「tobi-seiji」。這種類型可以在圖版 19、21、22、23、25 和 28 中看到。

其中,圖版 28 上的鐵褐色斑紋青瓷盒與蓋是充分發揮了這種類型的特點的崇高作品。這件作品的造型當然是一流的,而現在只有很少的可比例子,這就使它更加重要。

Black glazed porcelain is another form found starting in the Eastern Jin. The addition of a powdered natural iron oxide to celadon glaze was used to create this ware type, with those from the Deqing kilns of Zhejiang province particularly famous. Black Glazed Chicken-Head Ewer at plate 24 is a black glaze item with few comparable works. Judging from the smooth black glaze and the body clay it was likely made at a kiln other than the Deqing kilns. The work is thought to date from the Southern Dynasties period. The small scale of the work also makes it a rarity.

The Southern Dynasties saw considerable changes in celadon. As previously noted, celadon was first produced in northern Zhejiang prefecture in the Eastern Han dynasty. Later, in the Three Kingdoms, Western Jin and Eastern Jin periods, celadon developed into what is now called Old Yue celadon, a distinctively mature and polished ware type. Then in addition to Zhejiang, celadon also began to be produced across quite a broad section of southern China, including Jiangsu, Hunan, Hubei and Jiangxi. Southern Dynasties celadon is thought to have emerged along the trajectory from Old Yue ware, but in terms of glaze, clay quality and design concepts, celadon developed a diversity not found in previous Old Yue ware. In such works we can sense a style that links to the celadons of later generations. Given these factors, we can also sense that these are different categories of celadon inconceivable in Old Yue ware.

黑釉瓷器是東晉開始出現的另一種形式。浙江德清窯的黑釉瓷器尤為著名。盤24的黑釉天雞壺是一件黑釉器物,很少有可比的作品。

從光滑的黑釉和胎土看,它很可能是德清窯以外的窯燒製的。本壺被認為是南朝時期燒製的。作品的小尺寸也十分罕見。

南朝青瓷有相當大的變化。如前所述,青瓷最早產於東漢時期的浙北地區。後來到了三國、西晉、東晉時期,青瓷發展成現在所說的古越青瓷,是一種獨特的成熟拋光器型。之後,除了浙江以外,中國南方的江蘇、湖南、湖北、江西等地也開始生產青瓷。

南朝青瓷被認為是沿著舊越器的軌跡出現的,但在釉色、泥質和設計概念方面,青瓷發展了舊越器所沒有的多樣性。在這些作品中,我們可以感受到與後代青瓷相連的風格。由於這些因素,我們也可以感覺到這些是古越器無法想像的不同類別的青瓷。

Southern Dynasties celadon is characterized by the glassy quality of its glaze pierced with tiny crazing, and the increase of works with bluish green or pale green colors, all accompanied by an increase in works with white body clay. There are more relatively white-toned celadons which can be seen as a white porcelain prototype ware. And yet there is also a lessening of quality that is not found in Three Kingdoms to early Eastern Jin period works, which meant a more frequent appearance of glaze loss or glaze pulling. In terms of decoration, the most striking feature is the extensive use of large, loosely expansive lotus blossoms. The lotus blossom and lotus petal motifs appear in line-cut incision, slanted-cut incision and three-dimensional methods (see fig. 1). This motif can be seen on plates 29, 30, 31, 32, 37 and 38, while plate 30 features a large lotus blossom drawn in fine incised lines across the center of the dish. This work represents the early period of the lotus blossom motif, in the stage prior to the development of broad-stroked, deep-carved images. Along with the rapid spread of this lotus blossom motif trend, there also began to appear works that had carved vining scrolls designs (see fig. 2). These decorative patterns are thought to have been influenced by the Buddhist art that accompanied the eastern expansion of Buddhism.

南朝青瓷的特點是釉面呈玻璃質,有微小的裂紋,藍綠或淡綠色的作品增多,伴隨著白胎作品的增多。白胎青瓷比較多,可以看成是白瓷的原型器。但也出現了三國至東晉早期作品所沒有的質量下降,即更多地出現失釉或拉釉現象。在裝飾方面,最突出的特點是大量使用寬鬆舒展的大型蓮花。蓮花、蓮瓣圖案以線刻、斜刻、立體等方式出現(見圖 1)。

此圖案可見於盤 29、30、31、32、37 及 38,而盤 30 的特色是在盤子中央以精緻的刻線畫出一朵大蓮花。這件作品代表了蓮花圖案的早期,也就是寬刻、深刻圖案發展之前的階段。隨著蓮花紋的迅速蔓延,也開始出現雕刻蔓草紋的作品(見圖 2)。這些裝飾圖案被認為是受到佛教東擴時佛教藝術的影響。

The differences in color and quality of body clay in Southern Dynasties celadon works indicate that they were made across a wide geographical area.

Similarly, there was an increasing trend towards the production of functional vessel shapes, such as cup and stand sets or a box containing several cups (plate 36, showing a box without a cover). However, the end of the Southern Dynasties period saw renewed fighting and wars, which meant that there are few materials dating from the mid oth century onwards. While that unfortunately means that it is hard to grasp the state of celadons during that period, we can hope that future studies will provide more understanding in this area.

南朝青瓷作品在顏色和胎土品質上的差異顯示它們是在廣闊的地理區域內製造的。

同樣地,功能性器皿形狀的製作也有增長的趨勢,如杯與座的組合,或一個盒子內裝幾個杯子(圖版 36,顯示一個無蓋的盒子)。然而,南朝末年戰爭再起,因此十世紀中葉以後的材料很少。可惜的是,我們很難掌握那時期的青瓷狀況,但我們希望未來的研究能提供這方面更多的了解。

Next let's consider the ceramics of the Northern Dynasties period. No noteworthy glazed ceramics have been excavated from Northern Dynasties sites that date from the Wei and Western Jin of the Three Kingdoms through the confusion of the Sixteen States period, until the Northern Dynasties began in the early 6th century. This dearth may have been influenced by the 205 decree by Cao Cao (155-220) forbidding "lavish burials", which led to a subsequent period of burials that involved fewer grave goods.

接下來讓我們考慮北朝時期的陶瓷。北朝遺址從三國魏晉到十六國的混亂時期,一直到 6 世紀初的北朝,都沒有出土值得注意的釉陶。這種匱乏可能是受到 205 年曹操(155-220 年)下令禁止「奢侈殉葬」的影響,導致後來墓葬中的殉葬品較少。

New movements in the production of glazed ceramics in northern China can be seen from the Northern Wei dynasty onwards. The Eastern Wei saw the production of celadon thanks to the importation of both ceramic workers and technologies from the Southern Dynasties. The following Northern Qi also produced distinctive works that represent new developments. The landmark examples of this new development are large jars that have three-dimensional, upward facing and downward facing lotus petal motifs lined up to completely fill the entire torso to the foot area of a vessel, topped by mold-made palmette and medallion forms derived from West Asian arts, applied to the neck and torso areas. A renowned work is from the Feng Zihui tombs in Jingxian, Hebei province, a site that bears an inscription dated 565. (fig. 3) The body clay on that work is gray and somewhat coarse in texture, with the blackened glaze which shows an olive or dark brown color in the glaze pooling. These factors indicate a different quality than that displayed in Southern Dynasties celadon. Similar examples have also been discovered in other regions such as Shandong, Henan and Hubei provinces.

Northern Dynasties ceramics are characterized by their extensive use of splendidly applied decorations. As the nomadic tribes established a succession of kingdoms in northern China, large numbers of cultural rarities, including gold or silver works, glassware and coins, were brought to China from the West along the Silk Road and grasslands. These items are thought to have had a massive influence on the ceramics styles and decorative designs of the day. The palmette motif, acanthus leaf motif and medallions are representative of transplanted designs (fig. 4). The acanthus motif seen on plate 48 Celadon Jar with Five Lugs and Applied Flower Design resembles the head nimbus on a central worship image (fig. 5) on the back wall of the South Cave, Northern Xiangtangshan caves, Hebei province. This is one example of how such motifs were used in ceramic designs.

Plate 51 uses thickly formed applied lion-mask motifs and flower-like groupings of hemispherical elements. This type is characterized by decoration made of karyôbinga (bird body/angel head) forms not found on other works, a vessel form reminscent of Northern Dynasties ceramics and, moreso than anything else, its compelling sensibility that matches its large scale. Plate 50 Brown Glazed Vase with Applied Ornaments dates to the Sui dynasty, and is an important example of how the Northern Dynasties applied decoration style developed in succeeding periods. These refined applied decorations then carried on and were used in the lovely works of the succeeding Early Tang to High Tang periods.

In general, Northern Dynasties ceramics were clearly based on the presence of southern Chinese ceramics and through their changes and developments in their respective regions they can then be seen as blossoming into the various types of ceramics created in the Sui and Tang dynasties.

北魏以後,中國北方的釉陶生產出現了新的動向。東魏時期,由於從南朝輸入陶瓷工人和技術,出現了青瓷的生產。隨後的北齊也產生了代表新發展的獨特作品。這種新發展的標誌性作品是大罐,其立體的向上和向下的蓮瓣紋排成一排,完全填滿了整個器物的軀幹到足部區域,頂部是模制的掌紋和徽章形式,源自於西亞藝術,應用在頸部和軀幹區域。河北景縣馮子惠墳墓出土了一件著名的作品,碑文刻於 565 年。(圖三)那件作品的胎土是灰色的,質地有點粗糙,釉色發黑,在釉池中呈橄欖色或深褐色。這些因素顯示本壺的質量與南朝青瓷不同。類似的例子在其他地區也有發現,如山東、河南和湖北省。

北朝陶瓷的特點是大量使用華麗的紋飾。由於游牧部落在中國北方建立了一連串的王國,大量的文化珍品,包括金銀器、玻璃器皿和錢幣,沿著絲綢之路和草原從西方被帶到中國。這些物品被認為對當時的陶瓷風格和裝飾設計產生了巨大的影響。

掌紋、刺桐葉紋和徽章是移植設計的代表(圖 4)。盤 48 青瓷五耳施花紋罐上所見的刺桐紋,與河北省北香堂山石窟南窟後壁中央供養像上的雲頭紋(圖 5)相似。這是這類圖案用於陶瓷設計的一個例子。

圖版 51 使用厚重的獅子面具紋和花朵狀的半球形元素組合。這類煙壺的特點是用其他作品所沒有的鳥身/天使頭飾,這種器形讓人聯想到北朝的陶瓷,而最重要的是其引人注目的感性與其大規模相匹配。

板 50 施釉褐彩瓶可追溯至隋代,是北朝施飾風格在其後發展的重要例子。這些精緻的貼花紋飾在繼承的初唐至盛唐時期的可愛作品中得到延續和使用。

總體而言,北朝陶瓷顯然是以中國南方陶瓷為基礎,並透過它們在各自地區的變化和發展,形成了隋唐時期的各種陶瓷。

Ceramic figurines were one type of northern Chinese ceramic product. The production of ceramic figurines flourished in the Northern Wei (439-534) and the Northern Qi (550-577). There was a rapid increase in the numbers of ceramic figurines produced after the Northern Wei moved their capital to Luoyang in 493. Very few of these figurines were glazed, with the majority painted with polychrome. The distinctive formal qualities characterized by sharpness and a sense of tension are the most fascinating aspects of Northern Wei figurines, and they are extremely popular as the pinnacle of ceramic figurine production. The faces of the human figurines are particularly noteworthy, with their thin, high arched eyebrows, almond shaped eyes with outer edges raised and slightly smiling lips known as the archaic smile. The Northern Wei became devout Buddhists, and these features were shared with the Buddhist sculpture of the period (fig. 6).

Plate 53 Painted Pottery Bureaucrat in this exhibition is a representative example of Northern Wei figurines. It would not be an exaggeration to state that its tall and lithe form and facial expression reminiscent of Buddhist sculpture is unpar-alleled in this figural form. Plate 56 Painted Pottery Man On Horseback is an easily likeable work thanks to the small head and thin short feet, which are specifically Northern Wei methods of distorting figures. In the following Northern Qi period the figurines show an overall rounder sensibility than that found in the Northern Wei.

In addition to Northern Wei works, this exhibition also features Western Jin figurines. Plate 52 Painted Pottery Warrior is an impressive work with the warrior's mouth open and teeth bared. Numerous examples of this type of work have been discovered in the Western Jin tombs centered around the Loyang region. There are, however, few that compare to the scale of this work, a feature that makes it all the more compelling.

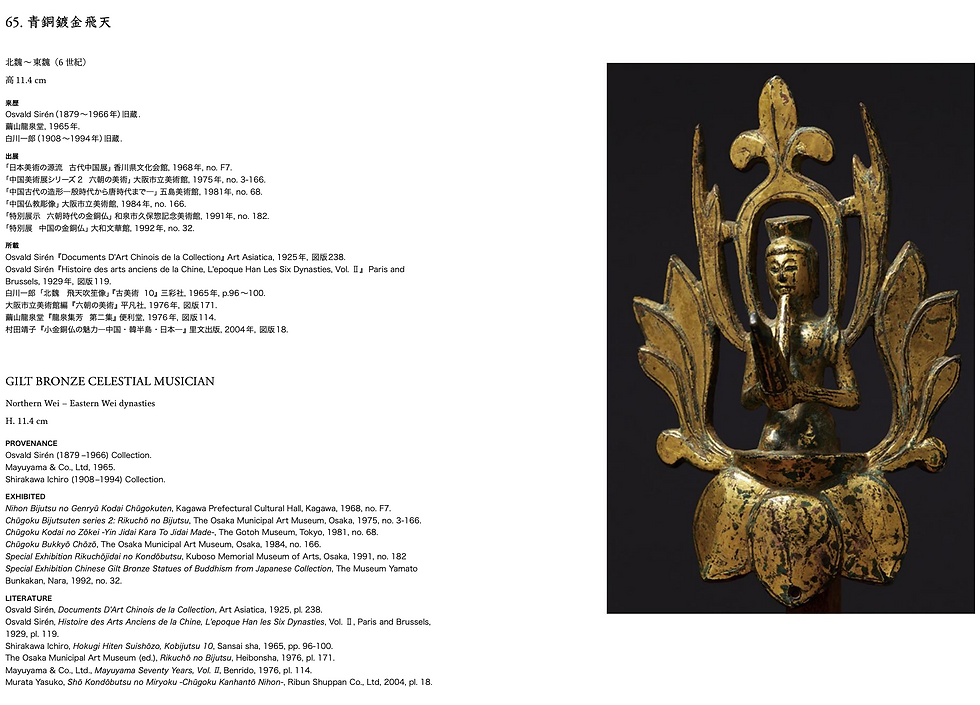

Along with ceramics, Buddhist sculpture was the other major art form of the Wei, Jin and Northern and Southern Dynasties periods. As Buddhist worship spread and deepened in the various states that make up the Sixteen Kingdoms pe-riod, gilt bronze images of single seated Buddhas, a style known as koshikibutsu in Japanese, flourished across China's northern region. This process brought about a variety of different styles, including small bronze and gold-plated works that were produced in considerable numbers throughout the Northern Dynasties period (Plates 63). The highly regarded works of this type were produced during the Wei Taihe era (477-499). Plate 64 Gilt Bronze Seated Buddha bears an inscription dated 464 (Northern Wei Heping 5). This is an extremely important work shows the koshikibutsu style that connects to Taihe era style Buddhist sculptures.

陶俑的生產在北魏(439-534 年)和北齐(550-577 年)非常興盛。北魏於 493 年遷都洛陽後,陶俑的生產數量迅速增加。這些陶俑很少有施釉的,大部分都是用多彩繪畫的。北魏陶俑最迷人之處在於其獨特的形式特質,其特點是銳利和張力感,作為陶俑製作的巔峰,北魏陶俑極受歡迎。北魏人俑的臉部尤其值得注意,他們的眉毛細而高彎,眼睛呈杏眼形,外緣上翹,嘴角微微含笑,被稱為 「古笑」。北魏人成為虔誠的佛教徒,這些特徵與當時的佛教雕塑是相同的(圖6)。

本展覽的圖版 53 彩陶官吏是北魏造像的代表。它高大而婀娜的形態以及令人聯想到佛教雕塑的面部表情,在北魏造像中是無與倫比的。圖板 56 彩陶騎馬人是北魏特有的扭曲人物形象的方法,由於頭小、腳細短,所以是一件很容易讓人喜歡的作品。其後的北齊時期的陶俑比北魏時期的陶俑整體上呈現更圓潤的感覺。

除了北魏的作品之外,本展覽也展出西晉的陶俑。圖板 52 彩陶武士俑是一件令人印象深刻的作品,武士張開嘴,呲牙咧嘴。在洛陽地區的西晉墓葬中發現了許多這類作品。然而,很少有比得上這件作品的規模,這一特點使其更加引人注目。

除了陶瓷之外,佛教雕塑是魏晉南北朝時期的另一種主要藝術形式。隨著佛教信仰在十六國時期各國的傳播與深化,鎏金青銅單身佛坐像(日文稱為 「越式佛像」)在中國北方地區蓬勃發展。這一過程帶來了各種不同的風格,包括在整個北朝時期大量生產的小型青銅和鍍金作品(圖版 63)。這類受到高度評價的作品是在魏太和時期(477-499)製造的。

圖版 64 鎏金銅佛坐像有 464 年(北魏和平五年)的铭文。這是一件非常重要的作品,顯示出與太和時期的佛教雕刻相連接的越伎風格。

The construction of Buddhist cave temples and grottoes flourished with the spread of Buddhism in northern China. The Northern Wei produced the caves at Yungang (plate 69), Longmen and Gongxian, while the Eastern Wei produced Tianlongshan and the Northern Qi, Xiangtangshan. In the process of cave temple production, large numbers of freestanding stone Buddhist images were created. Renowned images include those made during the Western Wei from huanghua stone, Northern Qi works in white marble and those excavated in Qingzhou, Shandong province. Plate 72 is a superb example of a Northern Qi white marble sculpture. The majority of these white marble sculptures were produced in Quyang prefecture, Hebei province.

Metalwork of this period was another important art form. While few extant examples exist, they are in a style that differs from Han and earlier periods, and can be seen as a separate genre. Plates 62 are small metal figures, but their intricately adroit handling reveal the full fascination of the metalwork from this period. Bronze vessels that feature the use of sahari (copper-tin alloy) and were wheel-formed are another art form of the Northern Wei and onwards period of the Northern and Southern Dynasties period that should not be overlooked. And it was through copying the forms of these sahari alloy works that potters of the period also made new developments in their own field. Plate 46 Green Glazed Jar is a good example of this process. At first glance its shape seems to be an imitation of a sahari work, and this indicates that it is an extremely realistic copy of such a work. This vessel shape can often be found in white porcelain from the Sui and Early Tang, but this work is an important example of an early green glazed jar with dish-shaped mouth given its faithful rendering of the sharpness of its metalware models and its black body clay that closely resembles that of Northern Wei figurines.

隨著佛教在中國北方的傳播,佛教石窟寺和石窟的建造也興盛起來。北魏創造了雲岡(圖版 69)、龍門和貢縣石窟,東魏創造了天龍山,北齊創造了響堂山。

在石窟寺的製作過程中,創造了大量的獨立石造佛教造像。著名的造像包括西魏黃花石造像、北齊白色大理石造像以及山東青州出土的造像。圖版 72 是北齊白色大理石雕像的絕佳例子。這些白色大理石雕刻大多產於河北省曲陽縣。

這個時期的金屬製品是另一種重要的藝術形式。雖然現存的例子不多,但它們的風格有別於漢代及更早的時期,可被視為一個獨立的流派。圖版 62 是小型的金屬人像,但其複雜巧妙的處理方式充分展現了此時期金屬工藝的魅力。

使用銅錫合金(sahari)的青銅器,是南北朝時期北魏以降另一種不容忽視的藝術形式。而這時期的陶工也是透過仿造這些銅錫合金作品的形式,在自己的領域上有了新的發展。圖版46 綠釉罐就是一個很好的例子。乍看之下,它的形狀似乎是模仿薩哈裡合金作品的,這表明它是對這種作品極為逼真的摹仿。這種器形常見於隋及初唐的白瓷,但鑒於本壺忠實地呈現了金屬器型的銳利,而且它的黑胎泥很像北魏的陶俑,所以它是早期青釉碟形口罐的重要例子。

2) The Collecting and Evaluation of Wei, Jin and Northern and Southern Dynasties Ceramics in Japan

Ceramics dating to the Wei, Jin and Northern and Southern dynasties first appeared in the marketplace at the beginning of the 20th century. This development was a result of the railway construction then occurring across greater China. The tombs and consumption sites within these construction zones were excavated, and through the activities of Europeans and Americans, items from those sites flowed into the Chinese art market from the latter half of the 19th century onwards.

The main phase of railway construction began in the 1880s led by Europeans and Americans who won the concessions to carry out the construc-tion. Within this activity the site that had the greatest influence on the art market was the Bianluo railway that ran for 183 km between Kaifeng, Henan province, and Luoyang. Work on this railway began in 1905 and was completed in 1909.

This region includes the east-west mountain range called Beimangshan, which was the site of a gathering of tombs dating from the Han to the Tang dynasty.

The Bianluo railway cut across the southern foothills of this mountain range and destroyed old tombs, which in turn led to a large number of burial goods being excavated. It is thought that Wei, Jin and Northern and Southern Dynasties ceramics were among the items excavated in this context.

The earliest of these burial goods dated to the Han, and continued on through the Sui to Tang dynasties. Laufer's Chinese Pottery of the Han Dynasty includes a preface that states that he surveyed Han dynasty grave goods in the three-year period between 1901 and 1904. The renowned English collector of Chinese ceramics, George Eumoropoulos, stated that he first saw grave goods in the London market in 1906, and their numbers increased from 1908 onwards.

In May 1910 the Burlington Fine Arts Club held its Early Chinese Pottery and Porcelain exhibition in London. This exhibition was important as the first display built around a core group of excavated ceramics. The display of Han and Tang burial goods were particularly noticed and praised by the ceramics aficionados of the time. These sources indicate that burial goods were first noticed in the market place in 1906, if not earlier. Their number increased by 1908 and by 1910 they had been actively taken up and become a major genre among Chinese ceramics collected for visual appreciation. And yet, these exhibitions and publications did not include any works from the Wei, Jin and Northern and Southern Dynasties.

The first introduction of Wei, Jin and Northern and Southern Dynasties ceramics came in 1916 when Luo Zhenyu published Celadon Funerary Urn (fig. 7) in his Guminggi tulu. This is an important example as the first introduction of an Old Yue ware piece.Ceramic figurines and their collection provide a good understanding of how Wei, Jin and Northern and Southern Dynasties ceramics were collected.

As noted above, burial goods began to circulate in the art market in 1906, and the collecting of ceramic figurines, a major form of grave goods, flourished.

The majority of these figurines dated to the Sui and Tang dynasties, and their appearance hastened the growth of collecting by Europeans and Americans. This market trend also affected Japan, and these figurines were gradually brought from around the time that the market picked up at the end of the Meiji period, and were received by Japanese collectors as a new genre. At first they were seen largely as reference works, but then in the early Taishô period they began to be collected as artworks. However, figurines from these periods were not mentioned in books during this period, from the end of the Meiji period through the early Taishô period. This reality is underscored by the fact that they did not appear in the important books of the time conveying a sense of early Chinese pottery, such as R. L. Hobson's Chinese Pottery and Porcelain (1915), the 1916 Guminggi tulu by Luo Zhenyu, or the 1915 Japanese publication, Seigai Ônishi's Shina bijutsu-shi chôso-hen (History of Chinese Art, sculpture volume). While so-called Six Dynasties burial goods were mentioned in other articles of the time, there were no photographs included and it is impossible to determine from their incomplete descriptions whether or not the works actually date to the Six Dynasties.

2) 日本魏晉南北朝陶瓷的收藏與評價

魏晉南北朝瓷器最早出現在市場上是在二十世紀初。這個發展是當時大中華地區鐵路建設的結果。十九世紀後半期開始,在這些建設區域內的墓葬和消費場所被發掘,通過歐美人的活動,這些場所的物品流入中國藝術市場。

鐵路建設的主要階段開始於十九世紀八十年代,由贏得特許經營權的歐美人帶領進行。其中對藝術市場影響最大的是汴洛鐵路,從河南開封到洛陽,全長183公里。這條鐵路於1905年動工,1909年完工。

這個區域包括東西走向的北邙山,是漢代至唐代陵墓的聚集地。

汴洛鐵路橫切這座山脈的南麓,破壞了古老的墓葬,進而導致大量的陪葬品被發掘。據推測,魏、晉及南北朝時期的陶瓷器也在出土之列。

這些隨葬品最早可追溯到漢代,一直到隋唐。Laufer 的《Chinese Pottery of the Han Dynasty》一書的序言指出,他在 1901 年至 1904 年的三年間調查了漢代的墓葬用品。英國著名的中國陶瓷收藏家 George Eumoropoulos 表示,他於 1906 年首次在倫敦市場上看到漢代殉葬品,從 1908 年開始,漢代殉葬品的數量不斷增加。

1910年5月,伯林頓美術俱樂部在倫敦舉辦了早期中國陶器和瓷器展。這次展覽很重要,是第一次以出土陶瓷為核心的展覽。展出的漢唐隨葬品尤其受到當時陶瓷迷的注意與讚賞。這些資料顯示,陪葬品在 1906 年(如果不是更早)就已經開始在市場上出現。它們的數量在 1908 年增加,到了 1910 年,它們已經成為中國陶瓷收藏中的一個主要流派。然而,這些展覽和出版物並沒有包括任何魏晉南北朝的作品。

1916年,羅振玉在《古明器圖錄》中發表了《青瓷神亭壺》(圖7),首次介紹了魏晉南北朝陶瓷。這是首次介紹古越器的重要例子。

陶俑及其收藏可以很好地了解魏晉南北朝陶瓷的收藏情況。如上文所述,1906年殉葬品開始在藝術市場流通,陶俑作為殉葬品的一種主要形式,其收藏也隨之興盛起來。

這些陶俑大多是隋唐時期的,它們的出現加速了歐美人收藏的增長。這種市場趨勢也影響到日本,這些陶俑大約從明治末期市場回暖時開始逐漸被日本收藏家接受,成為一種新的流派。起初,它們主要被視為參考作品,但到了大正初期,它們開始被當作藝術品收藏。

然而,從明治末期到大正初期,這段期間的書籍中並沒有提及這些時期的陶俑。這一現實的強調是,它們並沒有出現在當時傳達早期中國陶器的重要書籍中,如 R. L. Hobson 的《中國陶器與瓷器》(1915 年)、羅振玉 1916 年的《古明器圖錄》或 1915 年日本出版的大村西崖《中國美術史雕刻卷》。雖然當時的其他文章也有提到所謂的六朝陪葬品,但都沒有附上照片,也無法從其不完整的描述中判斷作品是否確實是六朝時期的作品。

The first clear example of the collecting of Wei, Jin and Northern and Southern Dynasties ceramic figurines in Japan can be seen in the catalogue of the art collection of the Tokyo Bijutsu Gakkô. This catalogue confirms that eight works were purchased in 1918, with 10 purchased in 1920, and others purchased later. The memoir of the art dealer Fukosai Hirota states that during the five-year period starting in 1917, "Around this time numerous Han, Six Dynasties and Tang figurines started to be seen in the market." Kôsaku Hamada published "Six Dynasties Clay Figurines" in 1921 in Kokogaku zasshi. Thus we can surmise that the collecting of Wei, Jin and Northern and Southern Dynasties ceramic first started in Japan in around the mid Taish period and quickly flourished.

Northern Wei figurines were particularly popular and collecting of such works flourished from that period through around 1935. It was primarily artists such as Nihonga painters, Western-style painters and sculptors who noticed and collected these items. It seems that there was a specific longing for Northern Wei figurines, and artists such as Kansetsu Hashimoto, Seihô Takeuchi and Yukihiko Yasuda all fought amongst themselves to acquire certain works. Dozens of 60 cm tall figurines of bureaucrats, a particularly large size for a Northern Wei figurine were excavated in the early Shôwa period and the majority of those are said to have been brought to Japan.

日本收藏魏晉南北朝陶俑的第一個明確例子,可以在東京美術館的藝術收藏目錄中看到。這本目錄證實八件作品是在 1918 年購入的,其中十件是在 1920 年購入的,其他的則是後來購入的。藝術商人 Fukosai Hirota 的回憶錄指出,在 1917 年開始的五年間,「大約在這個時候,市場上開始出現許多漢俑、六朝俑和唐俑」。濱田耕作 (Kôsaku Hamada) 於 1921 年在《國學雜誌》上發表了《六朝泥塑》。因此我們可以推測,魏晉南北朝陶瓷的收藏大約在大正中期開始在日本興起,並迅速繁榮。

北魏的陶俑尤其受歡迎,從那時到 1935 年左右,這類作品的收藏非常興盛。主要是日本畫家、西洋畫家和雕刻家等藝術家注意到並收藏了這些物品。橋本関雪、竹内栖鳳、安田靫彦等藝術家都為了獲得某些作品而互相爭奪。昭和初期出土了數十個高 60 公分的官僚俑,對於北魏俑來說是特別大的尺寸,據說其中大部分都被帶到了日本。

Kôka Yamamura was particularly attached to these figurines and held an auction of his own collection at the Tokyo Bijutsu Club in 1940, including a total of five of these large-scale bureaucrats figurines. Plate 53 Painted Pottery Bureaucrat is one of those five, and later was in the Yukihiko Yasuda collection. The splendid visage on this figure clearly indicates why this work was so fancied by collectors.

The collecting of such Northern Wei figurines in Japan exceeded its Western counterparts in terms of both quality and quantity. We can surmise that the similarity between Northern Wei figurine features and those of Japanese Buddhist sculptures inspired this trend.

山村耕花對這些陶俑特別有感情,1940 年他在東京美術俱樂部舉辦了一次自己收藏的拍賣會,其中一共拍賣了五件這樣的大型官僚陶俑。圖版 53 「加彩官人」是其中之一,後來為安田靫彦所收藏。這件俑的壯麗面容清楚地說明了為什麼這件作品如此受到收藏家的青睞。

在日本,這類北魏造像的收藏無論在質與量上都超越了西方的同類作品。我們可以推測,北魏造像的特徵與日本佛教雕刻的特徵相似,因而啟發了這股趨勢。

In terms of Old Yue ware collecting, as noted above, while Luo Zhenyu published one work in his 1916 Guminggi tulu, there were none included in Hobson's 1915 Chinese Pottery and Porcelain. These lacunae suggest that this type of items appeared later than other excavated wares. While it is surmised that the appearance of burial goods on the market was caused by the building of the railroads, the earliest full work on railroad construction in the Jiangnan region was the Huhangyong railroad. This railway extended 470 km from Shanghai to Hangzhou to Ningbo. The Shanghai to Hangzhou section began operations in August 1909, with the Hangzhou to Ningbo section operational in January 1914.

Given that the construction work in the area from Hangzhou through Shaoxing and Yuyao to Ningbo, an area closely connected to the excavation of Old Yue ware was prior to 1914, this means that there was about a five-year time lag between this section of work and the construction period of the Bianluo railway. And yet it would be overly hasty to say that this was the reason for the later appearance of Old Yue ware in the marketplace. Given that it seems that a high quality group of works were excavated from old tombs in the Nanjing region, it could be that either this area had not yet been excavated in the 1910s, or that if by that time a few had been excavated, their small number made them hard to evaluate and be received by the marketplace.

在古越器的收藏方面,如上所述,雖然羅振玉在其 1916 年的《古明器圖錄》中發表了一件作品,但在 Hobson's 1915 年的《Chinese Pottery and Porcelain》中卻沒有收錄。這些缺失說明這類器物比其他出土器物出現得晚。雖然有人推測隨葬品在市場上的出現是由於鐵路的建設,但江南地區最早的鐵路建設工程是滬杭甬鐵路。這條鐵路從上海到杭州再到寧波,全長 470 公里。上海至杭州段於 1909 年 8 月開始營運,杭州至寧波段則於 1914 年 1 月開始營運。

鑑於杭州經紹興、餘姚至寧波一帶與舊越器發掘有密切關係的工程是在 1914 年之前,這表示這段工程與汴洛鐵路的施工期間有大約五年的時間差距。然而,如果說這是古越器較遲出現在市場上的原因,那就太草率了。鑒於南京地區的古墓出土了一批質量很高的作品,可能是1910年代這一帶還沒有出土,也可能是當時出土了一些,但數量少,難以評價,難以被市場接受。

In addition to the shinteiko published in the Guminggi tulu, volume 1 of The George Eumoropoulos Collection Catalogue of the Chinese, Corean and Persian Pottery and Porcelain (1925) published a celadon lion-shaped vessel. However, an important point is that there were no Old Yue ware works published in the catalogue for the International Exhibition of Chinese Art held in London in 1935-1936.

This exhibition was an unprecedented and large exhibition that included a group of works excavated in the early 20th century. If Old Yue ware was appearing in the market place at that point, then undoubtedly it would have appeared in this exhibition. Another fascinating example occurred in 1923 when a number of Old Yue ware works were excavated in Xinyang, Henan province. These examples and the fact that the excavation sites for Old Yue ware covered the northern Chinese range of Shandong, Henan and Ningbo indicate that the shinteiko published in the Gumingqi tulu, and the lion published in volume 1 of The George Eumorfopoulos Collection Catalogue of the Chinese, Corean and Persian Pottery and Porcelain (1925) have the potential for excavated works in northern China. In this manner, given the background that the emphasis was on northern China in the state of excavated works at the time, we can consider that the Old Yue ware works that appeared on the market at this time had been excavated in northern China.

除了《古明器圖錄》所發表的神亭壺之外,The George Eumoropoulos Collection Catalogue of the Chinese, Corean and Persian Pottery and Porcelain (1925)第一卷也發表了一件青瓷獅子形器。然而,重要的一點是,1935-1936 年在倫敦舉行的中國藝術國際展覽的目錄中沒有發表古越器的作品。

這次展覽是史無前例的大型展覽,包括了一批二十世紀初出土的作品。如果古越器在那個時候出現在市場上,那麼毫無疑問地,它會出現在這個展覽中。另一個有趣的例子是 1923 年在河南信陽出土的一批古越器。這些例子以及古越器的出土地點涵蓋山東、河南、寧波等華北範圍的事實,都說明《古明器圖錄》所刊載的神亭壺,以及《喬治-尤莫夫普洛斯珍藏中國、科倫、波斯陶器與瓷器目錄》(1925)第一卷所刊載的獅子,都有可能是華北地區的出土作品。這樣,考慮到當時出土作品的狀態是以中國北方為重心的背景,我們可以認為這時出現在市場上的古越器作品是在中國北方出土的。

It is thought that Old Yue ware began to fully enter the marketplace around the time of the 1935-1936 exhibition in London. Examples of such positioning in the market can be seen in the July 1935 discovery by Yûzô Matsumura then Japanese consul in Hangzhou, of the kilns in Jiuyanzhen, Shaoxing. He described those kilns in his article "Expedition Records of Old Kiln Sites in Hangzhou" (Tôji vol. 8 no. 5), "Kiln sites were recently discovered in Jiuyan in Shaoxing prefecture, and the excavated items from those sites are said to have been taken to the Hangzhou market as Yuyao products." Further, according to Zhang Pikang's "Survey Notes Regarding Old Items Excavated at Shaoxing (Wenlan xuebao Vol. 3 No. 2), in March 1936, a large number of celadons were excavated during work on a road for military use in Shaoxing, primarily in Nanchi city about 4 km south of Shaoxing, and Keqiaozhen, about 12 km northwest of Shaoxing. The number was massive and the vessel types varied, noting that they were old-fashioned celadons with an unconstrained and artistic sensibility.Further in the spring of 1942 excavations were conducted at Yuhuatai, Nanjing.Yuhuatai is home to a massive number of old Six Dynasties tombs, centering on those from the Eastern Jin. A large number of the celadons excavated in this area appeared at one time in Nanjing antique shops.

一般認為,古越器大約在 1935-1936 年倫敦展覽時開始全面進入市場。1935年7月,當時的日本駐杭州領事松村雄蔵發現了紹興九巌鎮的窯。

他在《杭州古窯址考察記》(Tôji 第 8 卷第 5 號)一文中描述了那些窯址:「最近在紹興縣九巖發現了窯址,據說從那些窯址出土的物品被當作餘姚產品帶到了杭州市場」。此外,根據張丕亢的《紹興出土古物調查記》(『文瀾學報』3巻2期),1936年3月,在紹興修軍用道路時出土了大量青瓷,主要是在紹興南面約4公里的南池和西北面約12公里的柯橋。數量龐大,器型各異,注意到它們都是古式青瓷,具有不拘一格的藝術感。1942 年春,在南京雨花台又進行了發掘。雨花台是以東晉為中心的大量六朝古墳的所在地。這一地區出土的大量青瓷曾一度出現在南京的古董店中。

In this manner it seems that the true Old Yue wares that can be confirmed today were excavated in large numbers from 1936 onward and shortly after that, many were brought to Japan. They then appeared to have become a noticeable presence in Japanese art markets in the 1940s. The previously mentioned Plate 28 Celadon Box and Cover with Iron-Brown Spots is a representative example of the Old Yue ware brought to Japan at an early stage. This work was published in January 1938 in the volume 1 of the Chinese section of Tôki zuroku as owned by Shintarô Gotô, head of the Zauhô publishing house. This work is particularly important not only for the excellence of its glaze quality and beauty, but also because its very early arrival in Japan makes it a landmark work in Japanese collecting of Old Yue ware. Plate 6 Celadon Chicken-Head Jar, at the time called Yuyao ware, was brought to Japan in 1935 and acquired by the Nobumori Ozaki, an authority in the field of Chinese ceramic study at the time. The celadon Chicken-Headed Ewer (fig. 8) today in the MOA Museum of Art is also highly likely to have been brought to Japan prior to World War II. In 1951 it entered Mokichi Okada's collection.

The collecting and appreciation of Chinese ceramics flourished in Japan during the Shôwa 30s to 40s (mid 1950s to mid 1970s). Old Yue wares collecting became more widely spread and one of the major types in that expansion.

這樣看來,今天可以確認的真正的古越器是從 1936 年開始大量出土的,之後不久就有很多被帶到日本。到了 1940 年代,這些器物似乎在日本的藝術市場上顯著地出現了。前面提到的 Plate 28 鐵褐色斑的青瓷盒與蓋是早期帶到日本的古越器的代表。

這件作品於 1938 年 1 月發表於《陶器圖錄 中國篇(上)》,是座右寶主宰的後藤真太郎所藏品。這件作品特別重要,不僅因為它的釉質優良、美麗,而且因為它很早就到達日本,使它成為日本收藏舊越器的標誌性作品。圖6 「青磁天鶏壺」,當時稱為餘姚窯,1935 年被帶到日本,由當時中國陶瓷研究領域的權威尾崎洵盛購得。現藏於日本MOA美術館的「青磁天鶏壺」 (圖 8) 也極有可能是在二次大戰前被帶到日本的。1951 年,它進入岡田茂吉的收藏。

昭和三十至四十年代(1950 年代中期至 1970 年代中期),中國陶瓷的收藏與欣賞在日本蓬勃發展。古越器的收藏變得更為廣泛,也是那種擴展中的主要類型之一。

Finally the Northern Dynasties ceramics, as noted above, include very few excavated works. The large scale jar with mold cut applied motifs, primarily lotus petals, across the entire vessel torso, like the previously noted work from the Fengzihui tomb, which is typical of Northern Dynasty ceramics, can be found in such museums as the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in America and the Ashmolean Museum in England, but it is not known when those works first appeared in the market. However, their dynamism and lovely expression did not appeal to Japanese collectors of the day and thus such works were not brought to Japan at the time of their excavation.

Wei, Jin and Northern and Southern Dynasties ceramics came to be noticed in Japan as post-war Japanese collections of Chinese ceramics matured to world-class levels. Many of the works were brought to Japan from overseas markets during the 1960s to 1980s. Further thanks to the excavations that have flourished in China since the latter half of the 1980s, an astonishing number of Old Yue ware, Northern and Southern Dynasties celadons and lead glaze wares have flowed into the marketplace.

最後,北朝的陶瓷,如上所述,出土的作品很少。像前面提到的封子繪墳墓出土的作品,是典型的北朝陶瓷,在美國的 Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art 和英國的 Ashmolean Museum 等博物館都可以找到這種大形的罐子,其模琢施彩的圖案主要是蓮瓣,橫跨整個器身,但不知道這些作品是什麼時候開始出現在市場上的。然而,它們的動感與可愛的表現方式並不吸引當時的日本收藏家,因此在出土時這類作品並沒有被帶到日本。

隨著戰後日本對中國陶瓷的收藏達到世界級水平,魏晉南北朝陶瓷才開始在日本受到關注。其中許多作品是在 1960 年代至 1980 年代期間從海外市場帶到日本的。此外,由於 1980 年代後半期以來在中國的發掘活動蓬勃發展,數量驚人的古越器、南北朝青瓷和鉛釉器流入市場。

Reference Bibliography

Atsushi Imai, Chûgoku no Tôji 4 Seiji, Heibonsha, 1997.

Noboru Tomita, "Taishôki wo chûshin to suru senkuteki Chûgoku kanshô

tôjiki korekushon no keisei to tokushitsu - Kindai Chûgoku kanshô

bijutsu seiritsu no shiza kara" [The Formation and Nature of the Pioneering Collections of Chinese Ceramics for Visual Appreciation Focusing on the Taishô Period - From the Vantage Point of the Modern Era's Establishment of Chinese Arts for Visual Appreciation], Tôsetsu Nos. 555-562, Japan Ceramic Society, 1999-2000.

Fujio Koyama, "Ko etsu ji ni tsuite" [Regarding Old Yue Warel, Sekai Tôji Zenshû, Vol. 8, Kawade Shobo, 1955.

Hiroshi Sofukawa, "Sangoku-Nanbokuchô no jidai to geijutsu" [The Era and Arts of the Three Kingdoms and Northern and Southern Dynasties], New History of World Art, Tôyô hen 3, Sangoku Nanbokuchô, Shôgakukan, 2000.

Keiko Nomura, "Sangoku-Nanbokuchô no Tôji" [Ceramics of the Three Kingdoms and Northern and Southern Dynasties Periods," New History of World Art, Tôyô hen 3, Sangoku Nanbokuch, Shôgakukan, 2000.

Toru Nakano, "Gi-Shin-Nanbokuchô no kôgei" [Decorative Arts of the Wei, Jin and Northern and Southern Dynasties], New History of World Art, Tôyô hen 3, Sangoku Nanbokuchô, Shôgakukan, 2000.

R. L. Hobson, Chinese Pottery and Porcelain, Vol. 1, 1915.

R. L. Hobson, The George Eumoropoulos Collection Catalogue of the Chinese, Corean and Persian Pottery and Porcelain, Vol. 1, 1925.

International Exhibition of Chinese Art, exh. cat., 1935.

10. Tadashi Kawashima, "Waga kuni ni okeru Chûgoku kanshô tôji no juyô to sono hensen" [The Reception of Chinese Ceramics for Visual Appreciation in Japan, and its Change: Late Meiji, Taisho and Early Showa Periods], Tôyô Tôji No. 42, 2013.

Comments