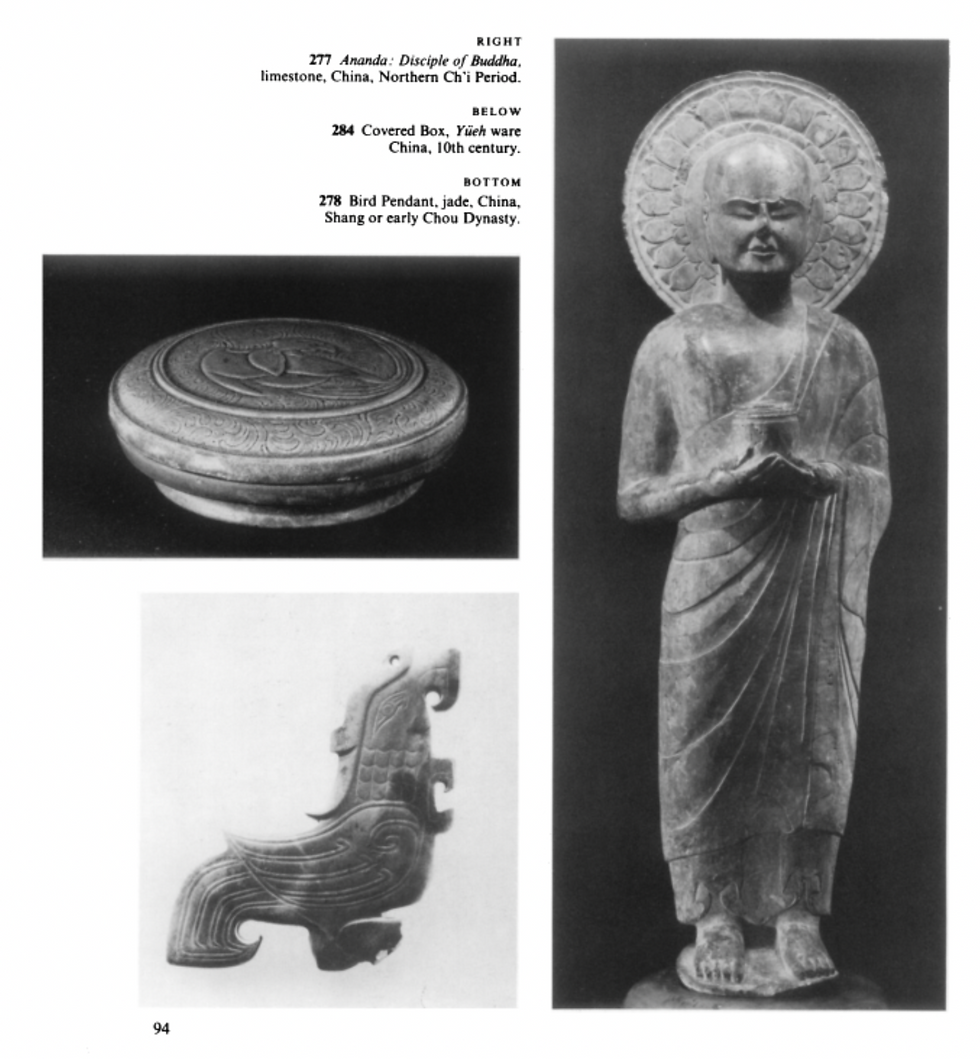

響堂山的佛教石窟寺群是北齊時期的核心成就,其中大部分的重要佛首都在海外。這尊響堂山弟子像早期被定為阿難,可能是因為其相貌年輕;但近期學者普遍認為是迦葉。有藏家指出,皺眉頭的是迦葉,微笑的通常才是阿難,這件是典型的響堂山的作品。

可以參考弗里爾美術館的響堂山阿難像:

圖片拍攝:frank lin

克里夫蘭博物館1972年由sherman lee購藏,這尊阿難像手持裝有舍利的聖物盒,象徵佛陀在死後進入最後的精神階段(涅槃)。簡約的藝術風格體現了此佛像的精神內涵。

響堂山石窟中有幾件類似的手持這種聖物盒的雕塑,這類盒子的功用現在基本被確定為佛舍利、或者佛祖的遺骨的容器。

There are several similar sculptures holding these sacred boxes in the Xiangtangshan Grottoes, and the function of these boxes is now largely recognised as that of containers for the relics of the Buddha, or the ashes of the Buddha.

Standing Disciple Mahakasyapa Holding a Cylindrical Reliquary

c. 550

(550-577)

Overall: 116 x 33 x 25 cm (45 11/16 x 13 x 9 13/16 in.)

Weight: 46 kg (101.41 lbs.)

Leonard C. Hanna Jr. Fund 1972.166

The complex of Buddhist cave temples at Xiangtangshan, “Mountain of Echoing Halls,” is a central achievement of the Northern Qi period.

Description

Mahakasyapa, the disciple of Shakyamuni, is presented with closed eyes in an expression of meditative concentration. He is holding a reliquary for the Buddha’s ashes, which symbolize the Buddha entering final spiritual attainment (nirvana) at death. The artistic simplicity exemplifies the spiritual content of this figure.

Provenance

Edgar Worch [1880–1972], Paris, France

by 1913–?

Victor Goloubew [1878–1945], Paris, France

November 10, 1972

(Étude Couturier et Nicolay, Hôtel Drouot sale, November 10, 1972, Paris, France)

1972

(Heim Gallery, Paris, France, sold to the Cleveland Museum of Art)

1972–

The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, OH

Citations

Musée Cernuschi. Collection Victor Goloubew. [Paris]: [Victor Jacquemin], 1913. Mentioned: no. 53, p. 18; Reproduced: pl. III

Mizuno, Seiichi 水野清一 and Toshio Nagahiro 長廣敏雄. Kyōdōzan sekkutsu: Kahoku Kanan shōkyō ni okeru Hokusei jidai no sekkutsu jiin. [響堂山石窟 : 河北河南省境における北齊時代の石窟寺院 = The Buddhist Cave-Temples of Hsiang-t'ang-ssu] Kyōto: Tōhō Bunka Gakuin Kyōto Kenkyūjo, 1937. Mentioned and Reproduced: p. 73

Lee, Sherman E. "The Year in Review for 1972." The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 60, no. 3 (1973): 63–115. Mentioned: no. 277, p. 114; Reproduced: no. 277, p. 94 www.jstor.org

Guo li gu gong bo wu yuan 國立故宮博物院. Hai wai yi zhen. fo xiang [海外遺珎. 佛像 = Chinese art in overseas collections. Buddhist sculpture]. Taibei Shi: Guo li gu gong bo wu yuan, 1986. Mentioned and Reproduced: pl. 52

Matsubara, Saburō 松原三郎. Chūgoku Bukkyō chōkoku shiron [中国仏教彫刻史論 = Research in the History of Chinese Buddhist Sculpture]. Tōkyō: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, 1995. Reproduced: vol. 2, pl. 450

Sun, Di, editor. Zhongguo liu shi hai wai Fo jiao zao xiang zong he tu mu [中国流失海外佛教造像总合图目 = Comprehensive Illustrated Catalogue of Chinese Buddhist Statues in Overseas Collections]. Beijing: Wai wen chu ban she, 2005. vol. 3, p. 624

Tsiang, Katherine R., and Richard A. Born. Echoes of the Past: The Buddhist Cave Temples of Xiangtangshan. Chicago: Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago, 2010. Mentioned and Reproduced: cat. no. 26, pp. 216–217

Cleveland Museum of Art. The CMA Companion: A Guide to the Cleveland Museum of Art. Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art, 2014. Mentioned and reproduced: P. 94

Exhibition History

Echoes of the Past: The Buddhist Cave Temples at Xiangtangshan. The David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, Chicago, IL (September 30, 2010-January 16, 2011); National Museum of Asian Art, Washington, DC (organizer) (February 26-July 31, 2011); Meadows Museum, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, TX (September 10, 2011-January 8, 2012); San Diego Museum of Art (February 18-July 22, 2012).

Year in Review: 1972. The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, OH (organizer) (February 27-March 18, 1973).

5è Exposition des Arts de l'Asie: Collection Victor Goloubew. Musée Cernuschi, Paris, France (1913–1914).

ECHOES OF THE PAST: THE BUDDHIST CAVE TEMPLES OF XIANGTANGSHAN

SEPTEMBER 30, 2010 – JANUARY 16, 2011

由芝加哥2004年發起的一個項目:

響堂山石窟最著名的展覽是Echoes of The Past,展覽提供了數字化的還原:https://asia.si.edu/whats-on/exhibitions/echoes-of-the-past-the-buddhist-cave-temples-of-xiangtangshan/

芝加哥大學響堂山數據庫:https://xts.uchicago.edu/content/exhibitions

概览

北齐时代 (550-577) 短暂的几十年中,有大量重要的艺术作品被创造出来。而代表了北齐艺术最高成就的是位于都城附近由皇家出资营建的响堂山佛教石窟群及其造像艺术。不幸的是,该石窟曾遭受过严重的破坏,其中的石刻造像流散到世界各地。响堂山项目一直致力于在北齐艺术与视觉文化以及中国佛教史的大背景中来理解石窟艺术。项目的构成和目标包括:1)开展合作研究 2)建设响堂山石窟、造像的图像信息数据库 3)通过石窟的数字重建、展览以及国际会议等方式分享研究成果。本网站作为项目成果的数据库将为今后的研究提供资料支持。相关的佛教经文及供养人题记的材料,请访问:https://xts-inscriptions.uchicago.edu/。

北齐响堂山石窟

响堂山石窟是一组从石灰石崖体中所开凿出的佛教石窟群,这些石窟中拥有丰富多样的石刻造像。位于今日河北省南部峰峰矿区和农业区的石窟群,由三十多个洞窟所组成,并且可以被分成三个主要部分。 此项研究主要针对可以追溯到北齐 (550-577) 的早期石窟,这些石窟代表了本地最卓越的凿刻成就。由于这些石窟位于作为政治和文化中心的北齐都城邺城的周边,响堂山早期洞窟的开凿,离不开宫廷皇室和朝臣的资助,以及在邺城地区活动的僧侣团体的指导。

窟群的两个主要部分可以分为北响堂山和南响堂山。位置偏北的北响堂山拥有皇室资助开凿的最早和最大的三个石窟,而南响堂山由七个较小的石窟所组成。第三个部分为水峪寺,也被称作“小响堂山”,此处由一座内部拥有石刻造像的北齐石窟所组成。石窟群拥有丰富的佛像,建筑结构,装饰细节以及许多的佛教刻经。这些内容不仅代表了当时多民族社会下的各种宗教思想和文化,而且体现了北齐皇室对佛教给予大力支持的成果。石窟的构思与设计和当时高僧的佛法造诣以及当地的民间宗教信仰有着密切的关系。石窟原址上关于六世纪开窟的文字记录已经所剩无几,只有一些关于后期开凿的洞窟的一些题记。其中一个 572 年的题记中提到了发愿刻凿佛经的事情。这些石窟的开凿始于北齐,这在一些记录新添石刻以及石窟修复活动的题记中提到过。结合这些文字与石窟本身的造像,并和一些其他的年代确切的北齐造像作比较,我们可以推测出这些石窟的年代为六世纪下半叶左右。

石窟现况与响堂山二十世纪简史

由于历史进程中石窟所受到的严重损毁,今天的响堂山已经无法向我们呈现出当初绚丽多彩的艺术成就了。在这些损毁当中,有一些属于时间的侵蚀和几百年来历史的沉淀,然而绝大部分是出于近代以来长期的人为破坏。二十世纪初,这些佛教造像的精湛艺术成就使它们成为文物商和为其服务的盗窃者的目标。最早对文物的劫掠是从1909 年开始的,清朝政府的覆灭和1911年中华民国的成立带来了极端的政治动荡。由于这些石窟远离城市,被当局所忽视,因此在数十年中,石窟内的文物受到了大面积的破坏。窟中大部分的独立造像 (free-standing images) 都已经被盗走,洞窟中的许多浮雕也被人为的切割窃取,剩下的石像也几乎没有头部和手部。

1913 年起,这些石像和造像残件逐渐开始出现在博物馆和私人收藏当中。其中许多大型雕像被刊登在 1914 年的伯灵顿杂志 (Burlington Magazine) 当中。这些石灰岩雕像的立体造型,大型规格和精美细部使它们成为许多西方和日本博物馆陈列中中国雕刻艺术的代表。目前已知的来自响堂山的一百多件造像和造像残件被散布到了欧洲、日本、台湾、美国的博物馆和私人收藏当中。关于石窟的最早照片大部分来自20 世纪 20 年代到 30 年代的日本摄影师,然而这些照片是在石窟被大面积损坏之后拍摄的。从照片中我们可以看到,为了保持其原有的宗教性质,石窟得到了一定程度的修复,然而新的塑像和修复后的头部与原先的效果相差甚远。这些照片是记录石窟现状的宝贵资料。第二次世界大战期间和建国初年,这些石窟受到了进一步的破坏。由于南响堂山位于彭城镇和峰峰矿区的边缘,因此在20世纪 50 年代,这里的石窟先是被设为一个军械库,之后成为一份当地日报的仓库。遗留下来得石像和残件也因此被挪出了石窟,导致这些石窟现在完全是空的。

近几十年来,响堂山石窟由峰峰矿区文物保管所负责其管理和文物保护。目前,对此处最大的威胁来自于环境污染。这些石窟位于农村矿区,这里有来自煤炭电厂、瓷窑和水泥厂的严重空气污染。酸雨和水泥厂带来的灰尘对石窟造成了可观的影响,尤其是临于峰峰矿区的南响堂山石窟。用于开采矿石的爆炸物也在威胁着附近水峪寺的安全。由于北响堂山的大型石窟位于村边的山上,因此这里和其他石窟相比,具有一定的地理优势。今日的北响堂山成为了人们经常拜访的宗教场所,人们来这里供奉神像并且每年都在此举办节日活动。

石窟与其内容

石窟与其内容可以被分为三个主要部分:1) 石窟建筑, 2) 石窟造像与布局, 3) 石窟刻经。

1)石窟建筑

从建筑构造上讲,这些石窟是根据一层或两层的穹顶式 “窣堵坡” (stupa) 而设计的。“窣堵坡” 是一种来自印度的用于埋葬佛舍利子的冢类建筑。在数个世纪的过程当中,随着佛教在亚洲的广泛传播,这种建筑也演变成了各种各样不同的形式。传说公元前六世纪,释迦牟尼圆寂之后,他的骨灰和舍利子被分别埋葬到七个窣堵坡当中。据说在公元前三世纪,印度的阿育王曾把这些骨灰和舍利再次分配并散布到了他的帝国各处。在这个传说中,阿育王创造了在一天之内建造八万个窣堵坡的奇迹。随着时间的变迁和地域的不同,这些窣堵坡的形态也在不断地发生变化:从最早的半球体的冢型结构,到砖石建造的有中央穹顶和顶部层伞的大型建筑,到密檐式木架构的塔型建筑都可以被找到。窣堵坡或塔逐渐成为了体现佛教寺庙的最显著建筑特征。北魏末期之塔主要是多层高耸的建筑形,其中最著名的便是坐落于北魏都城洛阳的永宁寺塔。据记载,它的高度可能达到了一千多尺。永宁寺塔初建于公元 516 年,却在公元 534 年毁于大火,这象征了北魏的灭亡。也许正是由于这个原因,东魏之后的塔建筑形式多以单层的 ‘覆钵” 形穹顶式结构存在。这个形式也许更接近于早期的阿育王式窣堵坡。在响堂山,窟前入口多是以石刻浮雕形式的仿木构造表现。有些窟前依然保留着窟廊,从这些前廊中我们依然可以看出一些抬梁式结构 (post-lintel structure) 的细部和用来支撑瓦檐的斗拱结构。这些窟前的特征集中体现在南响堂山的第七窟。石窟内部的石壁上,附近的山崖上,以及这个地域的其他佛寺中,都刻有许多这样的浮雕式的小型覆钵塔形佛龛。这样的小型覆钵塔还出现在许多同时代的石窟门额处,以及佛教石碑当中的佛像或的上面,以空中悬浮或天人托举的形式出现。

2)石窟造像

窟内的主像多为设在中心柱上或洞窟石壁上的佛教造像。按其内部结构划分,响堂山石窟主要可以被分为两种:一种是中心柱石窟,另一种为三壁三龛石窟。在后者当中,佛像被分别设置在窟壁上的三个较大的佛龛当中,或壁脚延伸出来的宝坛上。主像由中间的佛像以及旁边二、四或六名侍从所组成,侍从立像中包括菩萨,弟子和辟支佛 (缘觉)像。虽然在结构上这些神像多和后面的窟壁山体连在一起,但却能体现出十分立体的效果。其中有一些石像原本是独立雕刻的,之后被设置在佛龛上的莲座和坐台上面。其他的附属神像,比如飞天伎乐、礼拜僧人、狮子、天王力士等,则以浮雕形式被刻画出来。这些神像位于供台前、窟顶与窟壁上以及洞窟入口处的崖面上等。除此之外,窟内还有支撑立柱的神兽、供养人像、天界景象以及佛传图像,此外还有许多浮雕形式的莲花、宝珠、香炉、千佛形象。能够进一步体现石窟图像丰富性的还包括造像背光、石柱、甬道上的许多装饰性的浮火焰和穿插的忍冬花纹云纹图案等。

3)刻经

石窟中的佛教刻经是响堂山的一个显著的创新之处,刻经的传统大约始于北齐时期的邺城地区,南响堂山与北响堂山均有刻经出现。值得一提的是,拥有大量刻经的北响堂山南窟也被称为“刻经洞”。从 568 年到 572 年,此窟是由北齐朝臣唐邕施刻经文的。施刻经文的习俗被传播到了北齐都城的周边地区,尤其是河北涉县的娲皇宫,由此至北齐末期,刻经活动也被传播到了中国北方的其他地区。在山东省所发现的刻经大多位于自然的环境当中并没有石窟,例如在泰山、铁山、岗山的摩崖石刻都出现在山体崖面、山坡或巨石之上。佛经是佛所说的法,因此被认为是如同舍利子一般的佛迹中的一种,为佛法的遗迹,因此佛教石窟是它们理所当然的安家之所。

历史背景

北齐时代 (550-577 年) 属于北朝时期 (420-589 年) 中国北方地区被非汉族的鲜卑人所统治的时代。这些鲜卑人在四世纪晚期通过军事力量最先建立了北魏政权,之后北魏被分隔为东魏和西魏,而东魏 (534-550 年) 被北齐政权所取代。在可以左右东魏皇位的权臣高欢的统治之下,东魏的东都被设立在邺城,位于今天的河北省南部的临漳县。高欢次子高洋于 550 年称帝后为文宣王,邺城也成为了北齐的首都。这个朝代由高欢的历代子孙所统治,却在577年覆灭于以长安为中心的,始于西魏的北周政权 (557-581年)。响堂山位于北齐都城邺的附近,并处在邺城和高家的权利基地晋城(今天的太原山西)之间的交通要道之上。于是我们可以推测,在东魏与北齐时期,作为朝臣和皇室宗亲的高家必定经常来往于这条交通要道。

北齐一直被认为是一个政治动荡而战事连连的朝代,然而这个短暂的王朝却在多元文化的影响下,达到了艺术的高峰。汉族或非汉族工匠与出资人的密切互动,以及多种艺术样式和影响的融合,创造了展新的、多元性的艺术形式。鲜卑贵族与武士,汉族官吏和艺匠,佛教僧侣(汉族或非汉族),以及外族商人,乐伎,和官方使节都是活跃于当时政治,宗教,文化,商业生活的重要社会组成部分。直到五世纪末,鲜卑贵族依然保持着与当地汉人贵族的通婚的传统。统治者有效地利用了汉族传统的农业系统来充实自己的粮仓,从而维持他们的武装力量。他们也在不断地吸收着源于不同民族的各种才能,用来巩固帝国政权,设计宫殿、寺庙、和陵墓,充盈奢侈品的拥有量,或提供宗教方面的指导。从艺术方面来讲,北齐是一个至关重要的时代,因为正是这个时期当中,绘画和雕塑艺术有了显著的发展。与此同时,许多知名的艺术家的名字也被录入了正史。(蒋人和)

The Northern Qi dynasty (550-577) produced a large body of important works of art during its brief existence. A central achievement of the period is the complex of Buddhist caves of Xiangtangshan and their stone sculptures and engraved inscriptions, created near the Northern Qi capital with official sponsorship. Unfortunately, the cave shrines are now severely damaged and the sculptures and fragments of carvings from the cave sites scattered around the world. The Xiangtangshan Project has sought to acquire a better understanding the caves in broader narratives of the art and visual culture of the Northern Qi period and of the history of Buddhism in China. Its components and objectives were to 1) to conduct collaborative research, 2) to create a digital database of images and information on the caves and sculptures of Xiangtangshan, and 3) to present of the results of research with digital reconstruction of the caves, an exhibition, and international conferences. This website serves as a database of the project's results and a resource for future research. A supplemental website for the Buddhist sutras and dedicatory inscriptions can be seen at https://xts-inscriptions.uchicago.edu/.

The Northern Qi Cave Temples of Xiangtangshan

Katherine R. TsiangThe Chinese Buddhist cave temples of Xiangtangshan, “Mountain of Echoing Halls,” are a group of worship halls or shrines hollowed from limestone cliffs with carved sculptural images. Near Handan, in the Fengfeng Mining District of southern Hebei Province, a total of about thirty caves are divided among three sites. This study focuses on the early caves, which can be dated to the Northern Qi dynasty (550-577) and which represent the major achievements of cave-construction in this area. Formerly situated in the vicinity of a political and cultural center, the Northern Qi capital at Ye, these caves were created with the support of the royal family and officials and the advice of Buddhist monks active in the area around the capital.

The two main groups of caves are known as Northern and Southern Xiangtangshan. The Northern Group, Bei Xiangtang, is the earliest and largest in scale and has three caves begun with imperial sponsorship; the Southern Group, Nan Xiangtang, has smaller caves numbered from one to seven; and a third site at Shuiyusi, also known as Xiao Xiangtang or “Little Xiangtang,” has one Northern Qi cave with sculptures. The caves were richly carved with images of Buddhist deities, architectural and ornamental details, and the texts of Buddhist scriptures. These elements can be understood to represent various religious concepts and cultural ideals of the multi-ethnic society of the time and to be the result of generous official sponsorship of Buddhism. Their conception and design are related to the scholarship and teaching activity of eminent monks of the time, and to popular religious beliefs and practices. No contemporary sixth-century record of the creation of the caves survives at the sites. One Northern Qi period inscription, dated 572, dedicates the engraving of Buddhist scriptures. Later inscriptions, carved to record additional work and repairs, mention the beginning of cave-making in the Northern Qi. Together with the carved images themselves and their relationship with other datable Northern Qi sculptures, they provide evidence for assigning these remarkable caves to the second half of the sixth century.

Current Condition and Brief Recent History

The rich and complex contents and artistic achievement of the Xiangtangshan caves is not readily surmised today because of extensive damage to the sites. Some of the loss is attributable to the erosion and natural events over the passage of the centuries, but the loss of sculptures has mostly been perpetrated by relatively recent human activity. The fine quality of the sculpted images made them a target of looters in service of the art market beginning in the early twentieth century. The plundering began around 1909 during the period of severe political upheaval that saw the collapse of the last imperial dynasty and the establishment of the Chinese republic in 1911. The relative isolation of the caves from urban centers left them vulnerable to large-scale pilfering over several decades. The free-standing images that were in the caves have mostly been removed, and many relief elements are missing, forcibly cut away. Nearly all of the heads and hands of the remaining images are gone.

Sculpted figures and fragments from the caves first began to appear in museum and private collections around 1913. Several large standing figures were published in the Burlington Magazine in 1914. The volumetric modeling, large scale, and fine detailing of these limestone sculptures makes them among the most impressive of Chinese sculptures in many museums in the West and in Japan. Around one hundred sculptures or fragments are known in museums and private collections in Europe, Japan, Taiwan, and the U.S. The first photographs known of the caves were mostly taken by Japanese photographers in the 1920’s and 1930’s, after extensive damage had already occurred and many sculptures removed. They show repairs that were made so that the caves could continue to function as religious sites, but the new figures and replacement heads were poor substitutes for the originals. The photographs are a valuable record of the condition of the caves in this period. During the Second World War and in the early years of the Peoples Republic the caves experienced further damage. Those at the Southern Group, located near the village of Pengchengzhen and at the edge of the coal-mining town of Fengfeng were used as storage for a munitions factory and then a people’s daily newspaper in the 1950’s. The remaining damaged sculptures and fragments were removed from some of the caves so that they are now virtually empty. Some still remain at the site.

In recent decades the cave sites have been under the official supervision and protection of the Fengfeng Mining District Office for Preservation and Management of Cultural Relics. Environmental pollution is now the most serious threat to their existence. The caves are situated in a rural coal mining area with severe air pollution from mining and the operation of coal-fueled electrical power plants, ceramic kilns, and cement factories. The combined effect of acid rain and cement dust has taken a visible toll, particularly at the Southern Group of caves on the on the edge of the town of Fengfeng. The use of explosives for quarrying stone in close proximity to the Shuiyusi caves was a threat to that site. The location of the monumental caves at the Northern Group on a mountainside above a rural village, gives this site an advantage over the other locations. It has continued to be a religious site where people make offerings to the images and where popular festivals take place annually.

The Caves and Their Contents

The caves and their contents can be discussed under three principal subject headings: 1] the architectural forms, 2] the carved images and their arrangements, and the 3] engraved scriptural passages.

1] Architecturally, the caves were designed as structures of one or two stories with a domed roof. These are a type of stūpa, constructions deriving from Indian burial mounds for the relics of the Buddha and developed different forms over the centuries with the transmission of Buddhism across the vast reaches of Asia. According to Buddhist textual sources, after the historical Buddha’s death in the sixth century BCE his ashes or relics were divided and buried in seven stūpas. In the third century B.C. the Indian emperor Ashoka divided these and distributed them across all of his empire. The legend of Ashoka credits him with the miraculous construction of 80,000 stūpas in a single day. The stūpas changed in form over time and across geographical regions from hemispherical mounds, to constructed stone and brick monuments with raised central domes surmounted by multiple layers of umbrellas to towering structures and multistory wooden buildings known as pagodas. The stūpa came to be the identifying feature of Buddhist temples and monasteries. In the late Northern Wei dynasty, stūpas took the form of a multistory structures that could rise to great heights, the most extreme case being the celebrated stūpa of the Yongning Monastery in the Northern Wei capital at Luoyang which was recorded to have been nearly a thousand feet high. Begun in 516, it burned down in 534 in a great fire that became a symbol of the fall of the dynasty. Perhaps for this reason the favored architectural type of stūpa beginning in the succeeding the Eastern Wei and through the Northern Qi was a modest single-story structure with domed roof, that may refer back to earlier, possibly Ashokan, prototypes. The remaining evidence of the exterior façades of most of the Xiangtangshan caves indicates that they were modeled on wooden architecture carved in stone with a domed roof shown in relief at the top. Some caves still have a porch preserved in front showing the details of post and lintel construction and bracketing to support a tiled eave over the entrance. These exterior features are best preserved at Cave 7 of the Southern Group. Many smaller relief stūpa-shaped niches are carved in stone inside the caves, on the mountainsides nearby, and at other temple sites in the region. Miniature domed stūpas also appear floating, or supported by flying divinities, above entrances to caves and above the main images of the Buddhas and other deities on Buddhist steles of this period.

2] The principal sculptures are groups of Buddhist images set on altars in the central pillars or against the walls of the caves. The interiors of the Xiangtangshan stūpa caves are of two principal types, the central pillar cave and the chamber with altars on three walls. In the latter type the images may be placed in three large niches set into the walls or on a continuous platform extending around the walls of the cave. The main image groups consist of a Buddha as central figure with two, four, or six attendants. The standing attendant figures include bodhisattvas, disciples and pratyekabuddhas. Sculptors carved most of the main images while hollowing out the space of the caves. Many figures have full volumetric forms in spite of being attached to the walls behind them. Others were originally carved in the round and then set into pedestals and thrones on the cave altars. Subsidiary figures appear in relief—heavenly apsarases and musicians, kneeling monks, lions, spirit kings, guardians, and rows of small “thousand Buddhas”, located on the front of the altars, on the back of niches, on walls and ceilings, in cave entrances and on the exterior facades. In addition there are fearsome monsters that kneel and support columns at the side of niches, donor figures, paradise scenes, and narrative episodes from the life of the Buddha. Other elements include fine relief carvings of lotus blossoms, precious jewels, incense burners. The richness of the imagery is further supplemented by ornamental floral, flame-like, and interlaced scrolling patterns that appear in the halos of figures, on pillars, and in doorways.

3] The engraving of Buddhist scriptures, or sūtras in stone is an important innovative feature of the Xiangtangshan caves. Northern Qi Buddhist devotees appear to have initiated his practice in the area of Ye. Sūtra engravings appear at both the Northern and Southern Groups of Xiangtangshan Caves. Most notably, the South Cave or “Cave of the Engraved Scriptures” at the Northern Group has extensive sutra engraving work that was sponsored by the official Tang Yong from 568-572. This practice spread to other sites in the area of the capital, most notably Wahuanggong in Shexian, Hebei, and from there to other parts of northern China by the late Northern Qi period. In Shandong province, most of the engravings are in natural settings without caves, on cliff faces, on the sloping sides of mountains, or on large boulders, as seen at Taishan, Tieshan, Gangshan and other locations. Sūtras are texts believed to have been teachings of the Buddha and are therefore a type of relics, relics of the Buddha dharma, and appropriately housed within or associated with stūpa caves.

Historical Background

The Northern Qi dynasty (550-577) was part of the medieval period known as the Northern Dynasties (420-589) when the northern part of China was controlled largely by non-Chinese Xianbei rulers who first established the Northern Wei dynasty in the late fourth century through military conquest. The Northern Qi patriarch Gao Huan established the Eastern Wei dynasty (534-550) after the fall of Northern Wei and was the power behind the Eastern Wei throne. He relocated the capital to Ye, in present-day Linzhang county, southern Hebei province. This was also the seat of the Northern Qi dynasty, declared in 550 by Gao Huan’s second son, Gao Yang (the Emperor Wenxuan r. 550-59). The dynasty lasted until 577, ruled by a succession of the sons and grandsons of Gao Huan until it was conquered by the Northern Zhou (557-581). The Xiangtangshan caves are located not far from the capital at Ye and on the road leading between Ye and Jincheng (near present-day Taiyuan, Shanxi province), the seat of power of the royal family. Members of the court used the palace and the military outfitting post at the Northern Xiangtang caves site for these regular trips.

Though regarded as a period of political unrest and continuing warfare, the brief Northern Qi period saw the arts flourish in a multicultural environment. The close interaction between Chinese and non-Chinese artisans, patrons, and artistic models and influences fostered new, often hybrid, art forms. Xianbei aristocracy and military leaders, Chinese officials, artists, Buddhist monks (both Chinese and non-Chinese), as well as foreign traders, entertainers, and official envoys were active participants in the political, religious, cultural, and commercial life of the time. By the late fifth century, the Xianbei aristocracy frequently intermarried with the local Chinese elite. The rulers made use of the traditional Chinese agrarian system to fill their granaries while maintaining their military strength. They sought out the talents of people of various cultural backgrounds to assist in administering their empire, to design and furnish their palaces, temples, and tombs, to supply them with luxury goods, and to provide religious guidance. The Northern Qi is artistically a very significant period when the arts of painting and sculpture flourished, and the names of famous artists are recorded in history.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

峰峰矿区文物保管所、芝加哥大学东亚艺术中心《北响堂石窟刻经洞—南区1、2、3号窟考古报告》北京:文物出版社,2013年. (Fengfeng Mining District Office of Protection and Management of Cultural Relics; and Center for the Art of East Asia, University of Chicago. 响堂山刻经洞报告The Cave of the Engraved Scriptures at Northern Xiangtangshang. Beijing: Wenwu Publishing House, 2013.)Handanshi wenwu baoguansuo. “Handan Gushan Shuiyusi shiku diaocha baogao [Report of the Investigation of the Shuiyusi Caves, Gushan, Handan],” Wenwu, 1987/4.Mizuno Seiichi and Nagahiro Toshio. Kyodozan sekkutsu. Kyoto, 1937.Tokiwa Daijō and Sekino Tadashi. Shina bukkyō shiseki [Buddhist Monuments in China], ( Tokyo: Bukkyō shiseki kenkyu-kai, 1924–31), v. 3.Tsiang, Katherine R., et al. Echoes of the Past: The Buddhist Cave Temples of Xiangtangshan. Chicago: The David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago, 2010._____.“The Xiangtangshan Caves Project: An Overview and Progress Report with New Discoveries,” Orientations, 38/6 (2007).

Comentários