三彩貼花瓶

東京國立博物館

橫河民輔 收藏系列

制作地:中国

唐時代・8世紀

高25.0 口径7.6 底径8.8

此優雅瓶形的設計靈感來自於從中亞傳入的金屬器原型。器身略為扁圓,瓶頸刻有三道弦紋,現藏於東京國立博物館,收錄於佐雅子等主編的《世界陶瓷藝術:隋唐篇》,第11卷,東京,1976年,第59頁,編號43。

根津博物館有一件類似,局部施以淡綠釉,其圖錄可見於《唐代陶瓷》,東京,1988年,第45頁,編號40。

此外,還有兩件頸部環繞水平圓肋的相似瓶子:其中一件收錄於《唐代藝術展:由洛杉磯郡立博物館主辦的美國藏品借展》,洛杉磯,1957年,第82頁,編號194;另一件則見於《中國陶瓷大系:漢唐陶瓷大全》,台北,1987-1989年,第451頁。

The shape of this elegant vase was inspired by metal prototypes that were introduced from Central Asia. A very similar vase, partly glazed in pale green, in the Nezu Institute of Fine Arts, is illustrated in Tang Pottery and Porcelain, Tokyo, 1988, p. 45, no. 40. See also, two similar vases with horizontal ribs encircling the neck, one illustrated in The Arts of The T'ang Dynasty: A Loan Exhibition organized by the Los Angeles County Museum From Collections in America, Los Angeles, 1957, p. 82, no. 194; the other illustrated in Zhongguo taoci daxi, Han Tang taoci daquan (Chinese Ceramics Series, Han and Tang Ceramics), Taipei, 1987-89, p. 451.

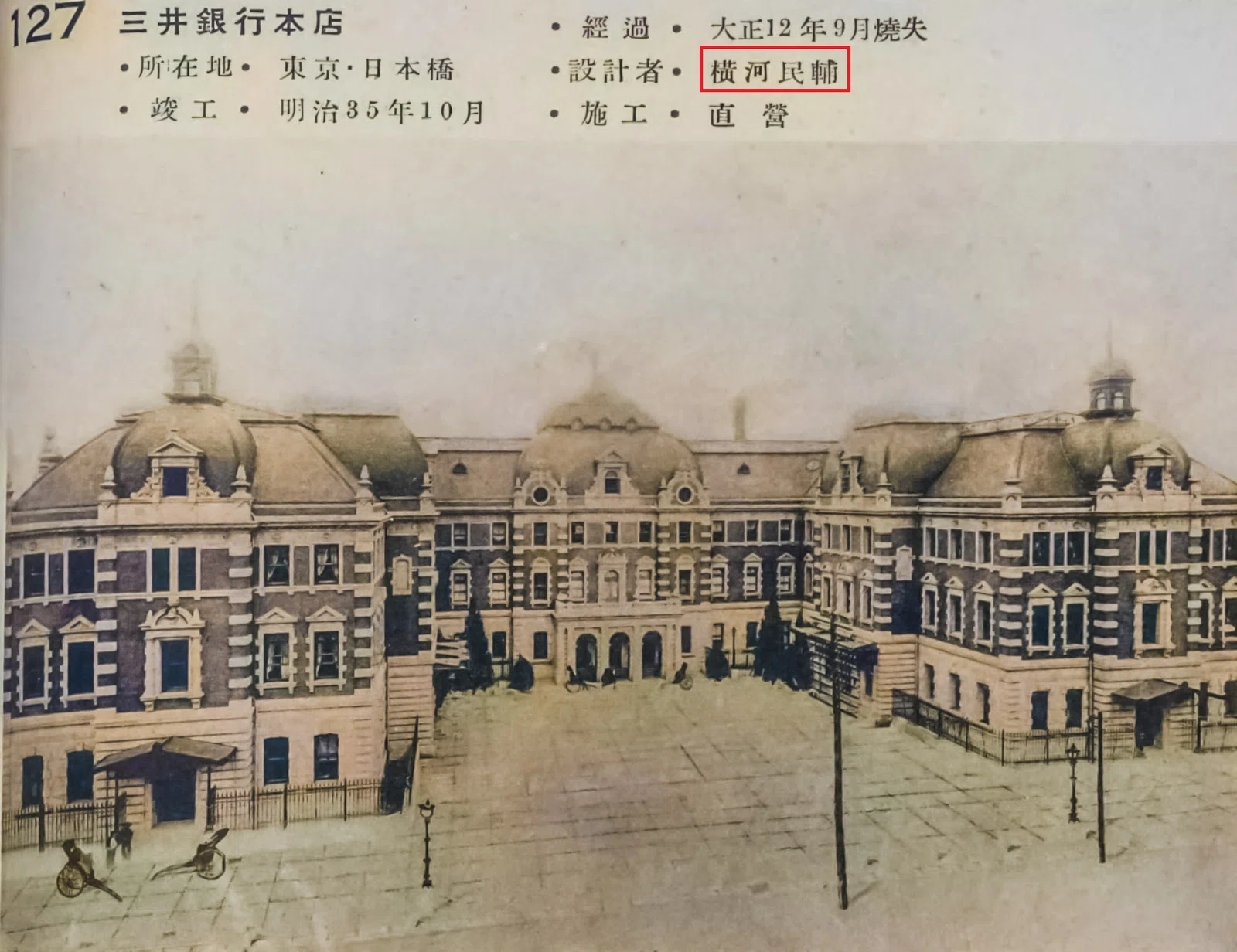

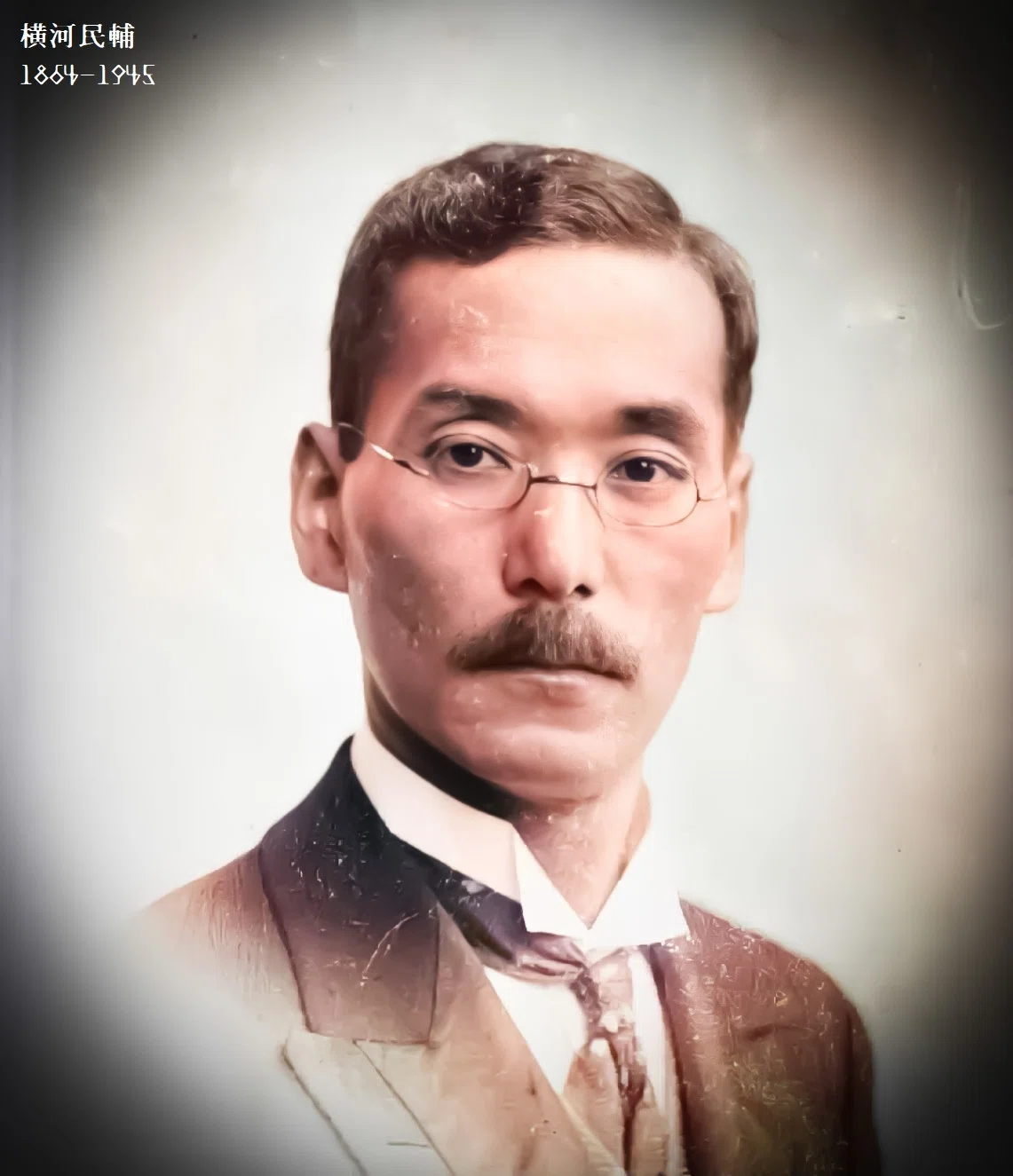

橫河民輔

1925年至1927年,橫河民輔擔任社團法人日本建築學會會長,並於1931年被推舉為名譽會長。1930年,他出任建築資料協會會長,直至1945年去世。1932年,他將其收藏的591件中國古陶瓷捐贈給東京帝室博物館,至1938年捐贈總數達到1068件。1935年3月,他創立了合資公司建築施工研究所。1938年8月,他設立了株式會社両全社,作為橫河集團的總部。1939年,他被任命為文部省國寶保存會委員。

美術論

橫河民輔因其對中國古陶瓷的收藏而聞名,後將這些藏品捐贈給東京國立博物館,形成著名的「橫河收藏」。

民輔的美術觀可從伊東忠太對其講演的反論中窺見端倪。1892年(明治25年)7月20日,橫河在造家學會例會中發表題為「東西美術孰優論」的演講。伊東隨後以《評橫河君之「東西美術孰優論」並述己見》為題進行逐條反駁。兩人的根本對立點不僅在於對美術的理解差異,更在於美術觀念上的分歧:

橫河的觀點:

「技藝乃世界共通之物,絕非某國或某地所專有。美術之目標,不應如政治家或軍人般,為局部或短暫的榮耀而努力,而應致力於讓人類因美術之恩惠而得以愉悅與喜樂,直到世界末日。」

伊東的觀點:

「東西方人種因風土氣候之異,其嗜好亦顯著不同。以吾論彼或以彼論吾皆無意義。彼方之美術代表彼方之風土,吾方之美術亦如是,雙方各循自身風土而生活,又何以論優劣?」

橫河的美術論或許在以文與武解釋美術原理上顯得過於傳統,但其試圖將美術從國家與榮譽中剝離的思維值得關注。他並非未回答東西美術優劣的問題,而是認為,只要有「讓人類長久愉悅於美術」的共同願望,古今東西的美術比較便無從爭論。

這一觀點亦可從帝國劇場的設計中得到佐證。在該劇場的建築風格爭議中,面對「採用西洋樣式還是日本傳統樣式」的選擇,橫河基於「為民眾服務的劇場」理念,毫不猶豫地選擇了設計西式劇場。

Tamisuke Yokogawa's Aesthetic Theory

Tamisuke Yokogawa is well-known for his collection of Chinese ancient ceramics, which he later donated to the Tokyo National Museum, forming the renowned "Yokogawa Collection."

Yokogawa's aesthetic philosophy is reflected in the critique by Itō Chūta of his lecture. On July 20, 1892 (Meiji 25), Yokogawa presented a lecture titled "On the Superiority of Eastern or Western Art" at a regular meeting of the Architectural Institute of Japan. Itō subsequently responded with a rebuttal titled "Evaluating Mr. Yokogawa’s ‘On the Superiority of Eastern or Western Art’ and Presenting My Opinions." The key difference between the two lies not only in their understanding of art but also in their fundamental aesthetic views:

Yokogawa's perspective:

"Art and craftsmanship are universal to humanity and not confined to any specific nation or region. Art should not be reduced to the fleeting ambitions of politicians or soldiers who seek temporary glory for limited purposes. Instead, it must aim to bring enjoyment and delight to humanity for all eternity, spreading its benefits to future generations."

Itō's perspective:

"Eastern and Western peoples differ greatly in their climates and natural environments, and thus their preferences vary significantly. It is futile for us to judge them or for them to judge us. Their art represents their environment, just as ours represents ours. Since each follows its own environment in shaping its way of life, how can we argue about superiority?"

While Itō’s argument reflects a more regional and relativistic view, Yokogawa's aesthetic philosophy reveals an aspiration to universalize art beyond national or cultural confines. Rather than directly addressing the question of superiority, Yokogawa implicitly argues that as long as there is a shared ambition for art to bring joy to humanity, comparisons of superiority become irrelevant.

Yokogawa's vision is further exemplified in his work on the Imperial Theatre. When faced with the debate over whether the theatre’s design should follow Western styles or traditional Japanese styles, Yokogawa, committed to the concept of a "theatre for the people," decisively chose to design the theatre in a Western architectural style.

橫河民輔美術論

民輔の美的感は、伊東忠太が民輔の講演(1892年〈明治25年〉7月20日、造家学会通常会)に対し、「横河君の『東西美術執れか勝る』論を評し併せて意見を述ふ」という題目の反論からわかる。このとき伊東は横河の美術についての理解を逐一反論するが、その基本的な対立点は両者の美術理解の差以上に美術観がつぎのようにことなっている。

(横河)夫よりは申度事は、総て技芸なるものは世界共有同案の物で御坐り升、之は彼の国、どに申すぺき狭少なるものではありません、政治家や、軍人などが全世界の一小部分の為に一瞬時の名誉のためにする様な稀な希望を保つべきものではありません、世界上に人間の有らん限り塵却未来まで、此美術に依って楽ましめ、喜ばせん、此技芸の恩沢に依らしめんと期せぎる可からず、(中略)。

(伊東)以上諭するか如く、東西人種は索と其の風土気候を殊にするを以て、亦甚たしく其嗜好を異にせり、是故に我を以て彼を論するに由なく、又彼を以て余を論ナるを持す…彼の美術は彼の風土之を代表せり、我の美術は我の風土之を代表せり、彼は彼の風土に従て生活し、我は我の風土に従て生活せり、然らは則ほち吾人亦何を以てか其優劣を争はんや、(中略)。

伊東のどこか鬱屈とした意識とは対照的に、民輔の美術論は、美術の原理を文と武とで説明するような甚だ旧式のものであったかもしれないが、美術を国家とか名誉とかと切り離して考えようとする志向がうかがえ、伊東の言うように東西美術の優劣について答えていないのではなく、上述の文で「世界上に人間の有らん限り塵却未来まで、此美術によって楽ましめ、喜ばせん」とする意欲が同じであれば、古今東西美術の比較は云うに抗しない、と答えている。帝国劇場の際に争われた、その建築を「西洋様式とするか、日本の伝統様式とするか」に対し「民衆のための劇場」として、躊躇なく洋式劇場を設計した。

Comments